노인 환자에서 입원 중 발생한 급성 담낭염의 임상 경과

Clinical Outcomes of Hospital-Acquired Acute Cholecystitis in the Elderly

Article information

Abstract

배경/목적

병원내 감염증에 있어 항생제의 선택은 지역 사회 획득 질환과는 차별화되어야 한다. 급성 담낭염은 노인에서 호발하는 질환으로서 초기 치료에 있어 항생제의 역할이 매우 중요한데, 일반적으로 노인 환자는 내성의 가능성이 높은 것으로 알려져 있다. 또한 동반 질환이 흔해 경우에 따라서는 선택적 치료인 담낭절제술의 시행이 쉽지 않을 수도 있다. 본 연구에서는 노인 환자에서 입원 중 발생한 급성 담낭염의 임상 경과에 대해 살펴보고, 일반적인 치료 원칙이 통용 될 수 있는지 살펴보고자 하였다.

방법

2006년 3월부터 2015년 2월 사이에 급성 담낭염으로 진단된 환자들에 대해 후향적 의무기록 분석을 시행하였다. 여타 질환으로 입원 중 급성 담낭염이 발생한 경우를 병원군으로 정의하였고, 응급실로 내원한 환자를 대상으로 연령 및 성별에 대하여 1:2 대응한 대조군을 구성하였다.

결과

40명의 병원군과 80명의 대조군 사이의 임상 경과를 비교하였다. 기초적 특성에 있어 병원군에서 만성 동반 질환이 더 흔하였던 것 이외의 차이는 없었다. 병원군의 경우 상태 의 악화로 인하여 초기 경험적 항생제를 교체해야 하였던 경우가 더 많았다(20.0% vs. 2.5%, p < 0.01). 회복까지의 기간도 병원군이 더 오래 소요되었다(23.3 ± 5.6 days vs. 10.1 ± 0.7 days, p = 0.02). 또한 병원군에서 조기 담낭절제술의 시행이 적었던 반면(7.5% vs. 40.0%, p < 0.01), 개복 전환은 흔하였다 (20.0% vs. 6.3%, p = 0.02).

결론

노인 환자에서 입원 중 발생한 급성 담낭염의 경우에는 항생제 치료 및 수술에 대한 일반적인 치료 원칙의 적용이 어려울 수 있으므로, 주의하여 접근하여야 한다.

Trans Abstract

Background/Aim

Antimicrobials for nosocomial infections are generally chosen discriminately from community-acquired diseases from concerns for resistance to which the elderly are highly exposed. The elderly are affected frequently by acute cholecystitis (AC), for which appropriate antimicrobial therapy is particularly important. Also, cholecystectomy for elderly patients with co-morbidities is expectedly not as feasible as for uncomplicated young patients. Characteristics of hospital-acquired AC in the elderly patients were investigated in this study.

Methods

Records of patients over 65 years and older diagnosed with AC between March 2006 and February 2015 were reviewed retrospectively. Hospital-acquired AC was defined as development of AC in patients who were admitted for other disorders. Community-acquired AC was defined as presence of AC at the time of admission. Community-acquired AC group (CG) was used as a control group that was matched for age and sex with a ratio of 1:2.

Results

There were 40 patients in hospital-acquired AC group (HG) and 80 in CG. Demographics did not differ except higher prevalence of underlying illnesses in HG. Necessity to change initial antimicrobials for worsening conditions was more common in HG than in CG (20.0% vs. 2.5%, p < 0.01). Time to recovery was longer in HG (23.3 ± 5.6 days vs. 10.1 ± 0.7 days, p = 0.02). Rate of early cholecystectomy was lower (7.5% vs. 40.0%, p < 0.01) and that of open conversion was higher (20.0% vs. 6.3%, p = 0.02) in HG.

Conclusions

For the elderly patients with hospital-acquired AC, antimicrobial and surgical management should be performed more meticulously since they showed distinct characteristics.

INTRODUCTION

The elderly are affected frequently by gallstones and the prevalence increases with age. About 15% of male and 25% of female aged over 70 years would have gallstones [1]. Among various gallstone-related diseases, acute cholecystitis (AC) is the most common and may be a life-threatening condition, especially in elderly patients. AC is an inflammatory condition of the gall bladder, which is causally attributable to stones in more than 90% of cases. Though dysmotility or ischemia might be involved, obstruction of the cystic duct by gallstones and subsequent bacterial infection are known to be pivotal in the pathogenesis of AC [2]. Therefore, appropriate antimicrobial therapy is of utmost importance in treatment of patients with AC.

Antimicrobials for nosocomial infections are generally chosen discriminately from community-acquired diseases from concerns for antimicrobial resistance. Especially, elderly patients are prone to be exposed to the health care system for multiple medical problems. The updated Tokyo Guidelines (TG13) for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis separated community-acquired versus healthcare-associated infections for the choice of antimicrobials, in which no specific regimen was recommended [3]. Also, it is expected that cholecystectomy for elderly patients, especially with co-morbidities may not be as feasible as for uncomplicated young patients. In this study, we investigated characteristics of hospital-acquired acute cholecystitis in the elderly patients and compared these characteristics to the characteristics of community-acquired acute cholecystitis.

METHODS

1. Patients and management protocol

The medical records of patients who were aged 65 years and older diagnosed with AC at a single referral center between March 2006 and February 2015 were analyzed retrospectively. Diagnosis of AC was made when clinical evidences of infection (fever or leukocytosis) and characteristic imaging findings were present in a patient who complained of or were suspected for having right upper quadrant or epigastric pain. Hospital-acquired AC was defined as development of AC in patients who were admitted for disorders other than AC. Community-acquired AC was defined as presence of AC at the time of admission. Community-acquired AC group (CG) was used as a control group that was matched for age and sex with a ratio of 1:2.

An unified management strategy was utilized throughout the study period. Third-generation cephalosporins were administered as the first-line antimicrobials unless the patient was allergic to penicillin. If the patient was allergic to penicillin, ciprofloxacin was used intravenously instead. Antimicrobial therapy was begun shortly after obtaining blood culture. The initial antimicrobials were changed into carbapenems in cases of clinical deterioration defined in the next section. Urgent laparoscopic cholecystectomy was considered as the principal treatment. However, high-risk patients, who were regarded to be intolerable for surgery, received percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC) initially and cholecystectomy was deferred. The Institutional Review Board approved this study and informed consents were exempted by the board.

2. Outcomes and definition

The primary outcome of this study was necessity to change the first-line antimicrobial agent, which was considered in cases of uncontrolled fever for 72 hours, isolation of a resistant pathogen, or development of major complications. Major complications, defined as dysfunctions in any one of the following organ/systems: hypotension requiring dopamine ≥ 5 µg/kg per min or any dose of dobutamine (cardiovascular system), disturbance of consciousness (nervous system), PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 300 (respiratory system), serum creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL (kidney), prothrombin time (international normalized ratio) > 1.5 (liver), platelet count < 100,000/mm3 (hematological system) according to the Tokyo guidelines [4]. The secondary outcome measures included time to recovery and any mortality within 30 days from the diagnosis. Time to recovery was defined as days elapsed from the initial diagnosis of AC to discharge or transfer to a department other than gastroenterology or surgery.

3. Statistical analysis

The differences of categorical variables between the groups were analyzed using the chi-square test with Yates’ correction or Fisher’s exact test when applicable. Means were compared using the Student’s t test. p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Mean values are expressed as means ± standard errors (SEs). Data were analyzed using R-software (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

There were a total of 40 patients in HG and 80 patients in CG during the study period. Mean time elapsed from the index admission to diagnosis of AC in HG was 33.7 ± 6.8 days.

The mean ages were 79.0 ± 2.0 years in HG and 78.6 ± 1.4 years in CG (p = 0.86) and male to female ratios were 20:20 and 38:42, respectively (p = 0.80). There was also no difference in the laboratory values at the time of diagnosis of AC, However, underlying chronic illnesses were more prevalent in HG than in CG (Table 1). The most common indication for admission in HG was cerebrovascular accident (40.0%), followed by infection (27.5%) and neurologic disorder (10.0%). Although the cases of acalculous cholecystitis tended to be more frequent in HG than in CG, the difference was not significant statistically (15.0% vs. 3.8%, p = 0.06).

Demographics and laboratory results of 120 consecutive elderly patients at the time of diagnosis of acute cholecystitis

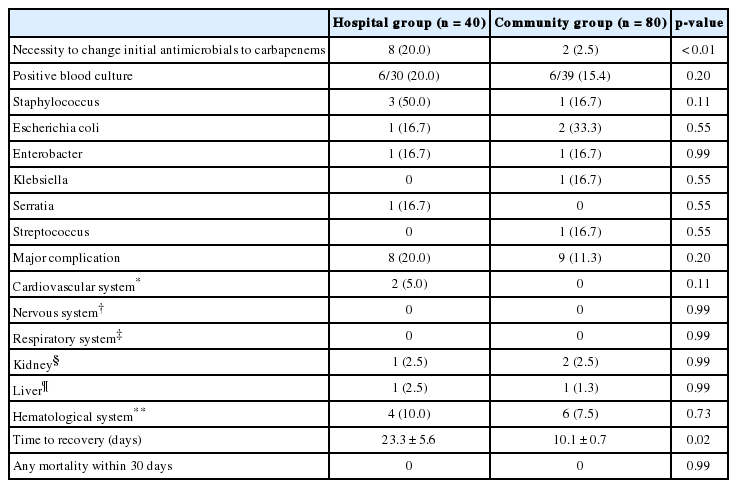

Necessity to change initial antimicrobials to carbapenems was more common in HG than in CG (20% vs. 2.5%, p < 0.01) although the results of bacteriological studies and development of major complications did not differ (Table 2). Also, time to recovery was longer in HG than in CG (23.3 ± 5.6 days vs. 10.1 ± 0.7 days, p = 0.02). There was no case of mortality within 30 days in both groups.

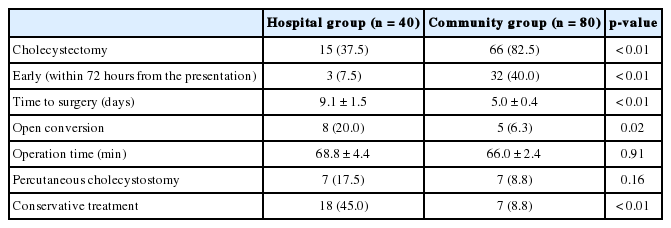

Comparisons of outcomes of interest between 40 patients with hospital-acquired acute cholecystitis and 80 with community-acquired cholecystitis in the elderly

Although cholecystectomy was performed in 66 (82.5%) out of 80 patients in CG, only 15 (37.5%) out of 40 could receive cholecystectomy in HG (p < 0.01) (Table 3). Early cholecystectomy, performed within 72 hours from the presentation, was less frequent (7.5% vs 40.0%, p < 0.01) and time to surgery was prolonged (9.1 ± 1.5 days vs. 5.0 ± 0.4 days, p < 0.01) in HG. In addition, conversion to open surgery was significantly higher in hospital group (20.0% vs. 6.3%, p = 0.02). There was no difference in operation time (68.8 ± 4.4 min vs. 66.0 ± 2.4 min, p = 0.91). Nine patients in HG and 10 in CG underwent PC and 7 (17.5%) patients in HG and 7 (8.8%) in CG improved without cholecystectomy (p = 0.16). There were 18 (45.0%) patients in HG and 7 (8.8%) in CG who recovered with conservative treatment.

DISCUSSION

The management of acute cholecystitis in the elderly presents specific challenges due to associated comorbidities, the severity of their presenting disease and a greater likelihood of suffering post-operative complications and prolonged hospital stay [5]. Hospital-acquired infections are defined by World Health Organization (WHO) as infections acquired in a hospital by a patient who was admitted for a reason other than infection [6]. It is estimated that 2 million patients suffer from hospital-acquired infection and every year and nearly 100,000 of them die by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [7]. Also, additional healthcare expenses of $4.5 billion per year are resulted by hospital-acquired infections [8]. Meanwhile, the elderly are highly exposed to antimicrobial resistance. They are the age population with the highest incidence of antimicrobial administration, together with the very young [9]. Also, instrumentation of multiple catheters is not unusual, predisposing to bacterial colonization and infections [10]. Despite of such importance, however, data is limited regarding hospital-acquired infections of the biliary system. Although the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) guidelines of complicated intra-abdominal infections described community-acquired infections and healthcare-associated biliary infections separately, there are no specific recommendations for the choice of antimicrobials [11]. The TG13 states that healthcare-associated AC shows different bacteriology from community-acquired disease apparently, emphasizing the higher prevalence of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and yeasts, in which no regimen was recommended, either [3].

In this study, there was no statistically significant difference in the bacteriological studies between the patients with community-acquired and hospital-acquired AC. This finding might have resulted from the small sample size since hospital-acquired AC is an infrequent condition. There were more cases, however, in which the initial antimicrobials were changed into carbapenems in HG due to deteriorating conditions. Additionally, the observation that time to recovery was significantly longer in HG than in CG implies that the choice of antimicrobials should be more discreet in the patients with hospital-acquired AC. In addition to the high risk of antimicrobial resistance, elderly patients tend to take anti-thrombotic agents due to cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases or be immune-compromised, in which cases cholecystectomy should be deferred.

The incidence of gallstone disease rises with age [12,13]. Since the elderly patients are prone to be affected with co-morbidities, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which is currently accepted as treatment of choice for AC, may be a serious burden for them [14]. For example, lower rate of laparoscopic completion, higher rate of postoperative complication and longer postoperative hospital stays were reported in patients aged 80 years and older [5,15]. PC is an established alternative for resolution of inflammation in patients with AC who have high surgical risks due to old age or serious co-morbidities [16,17]. Although the difference was not meaningful statistically, more patients recovered after PC without cholecystectomy also according to our data, which might explain longer time to recovery in HG.

In addition to the small sample size, there are several limitations in this study. Firstly, in general, more cases are attributed causally to acalculous cholecystitis in the elderly, especially for those with serous co-morbidities. These might explain why more patients in HG were treated conservatively, which may be different from the standard strategy. Secondly, Data about concurrent infections or use of antibiotics prior to diagnosis of AC was not available. Lastly, there was no data regarding the recurrence in patients who did not receive cholecystectomy. A recently-published retrospective study stated that around one third of non-surgical patients experienced recurrence [18].

In conclusion, for the elderly patients with hospital-acquired AC, antimicrobial and surgical management should be performed more meticulously since they showed features distinct from those with community-acquired AC and there may be higher necessity for the use of carbapenems.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflicts to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Ho Jung Lee for providing English proofreading of the manuscript.