원발성 경화성 담관염과 원발성 담즙성 담관염의 최신 지견

Novel Insights of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis and Primary Biliary Cholangitis

Article information

Abstract

원발성 경화성 담관염과 원발성 담즙성 담관염은 모두 면역 반응을 매개로 하는 만성 간질환이다. 원발성 경화성 담관염은 담관의 염증과 섬유화로 인한 다발성 담관 협착을 특징으로 하는 질환으로 대부분의 경우, 비대상성 간경변증으로의 진행으로 인해 간이식을 필요로 하는 질환이다. 대부분의 원발성 경화성 담관염의 진단에서 영상학적 소견을 통한 특징적인 담관 협착 소견이 중요하다. 원발성 경화성 담관염의 경우, 대부분 염증성 장질환이 동반되어 있고 담관암과 대장암의 발생 위험이 크게 증가하는 것으로 알려져 있다. 원발성 경화성 담관염에서 질병의 진행을 늦출 수 있는 것으로 입증된 약물 치료는 아직 없는 것으로 알려져 있고, 담관 협착으로 인한 급성 담관염이 발생하거나 임상적으로 담관암이 의심될 경우, 내시경 시술을 통한 조직 진단과 담관 배액이 필수적이다. 원발성 담즙성 담관염은 자가면역 기전의 담즙 정체성 만성 질환으로 적절한 치료를 하지 않으면 비대상성 간경변증으로의 진행으로 간이식을 필요로 하는 질환이다. 원발성 담즙성 담관염의 진단은 담즙 정체성 간염 소견과 특징적인 자가면역항체의 양성 소견으로 이루어진다. 원발성 담즙성 담관염의 임상 경과는 환자들에 따라 매우 다양하므로 적절한 치료가 시행되기 위해서는 약물 치료 전과 후의 위험도 평가가 필수적이다. 우르소데옥시콜산과 오베티콜릭산과 같은 약물 치료는 원발성 담즙성 담관염에서 간경변증으로의 진행을 늦추어 예후를 개선시키는 데 중요한 역할을 하는 것으로 알려져 있다.

Trans Abstract

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) are immune-mediated chronic liver diseases. PSC is a rare disorder characterized by multi-focal bile duct strictures and progressive liver diseases, in which liver transplantation is required ultimately in most patients. Imaging studies such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography have important role in diagnosis in most cases of PSC. PSC is usually accompanied by inflammatory bowel disease and there is a high risk of cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal cancer in PSC. No medical therapies have been proven to delay progression of PSC. Endoscopic intervention for tissue diagnosis or biliary drainage is frequently required in cases of PSC with dominant stricture, acute cholangitis, or clinically suspected cholangiocarcinoma. PBC is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune cholestatic liver disease, which when untreated will culminate in end-stage biliary cirrhosis requiring liver transplantation. Diagnosis is usually based on the presence of serum liver tests indicative of a cholestatic hepatitis in association with circulating antimitochondrial antibodies. Patient presentation and course can be diverse in PBC and risk stratification is important to ensure all patients receive a personalised approach to their care. Medical therapy using ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) or obeticholic acid (OCA) has an important role to reduce the progression to end-stage liver disease in PBC.

서 론

원발성 경화성 담관염(primary sclerosing cholangitis)은 원인 미상으로 발생하는 지속적인 담관의 염증과 섬유화를 특징으로 하는 담즙 정체성 만성 간질환이고, 원발성 담즙성 담관염(primary biliary cholangitis)은 서서히 그리고 지속적으로 진행되는 간내 작은 담관의 파괴로 인해 답즙과 여러 독성물질들이 간에 축적되어 담즙 정체 상태를 보이게 되고, 결국 이로 인해 간세포 파괴 및 섬유화, 궁극적으로는 간경변증으로 진행하게 되는 자가면역 질환이다. 두 질환 모두 발생률과 유병률이 비교적 낮지만, 임상적으로 또는 혈액 검사 상 담관 폐색이나 담즙 정체가 의심될 경우, 반드시 감별을 해야 하는 질환이다. 본고에서는 원발성 경화성 담관염과 원발성 담즙성 담관염의 전반적인 최신 지견에 대해 최근의 문헌과 종설들을 근간으로 해서 정리를 해보고자 한다.

본 론

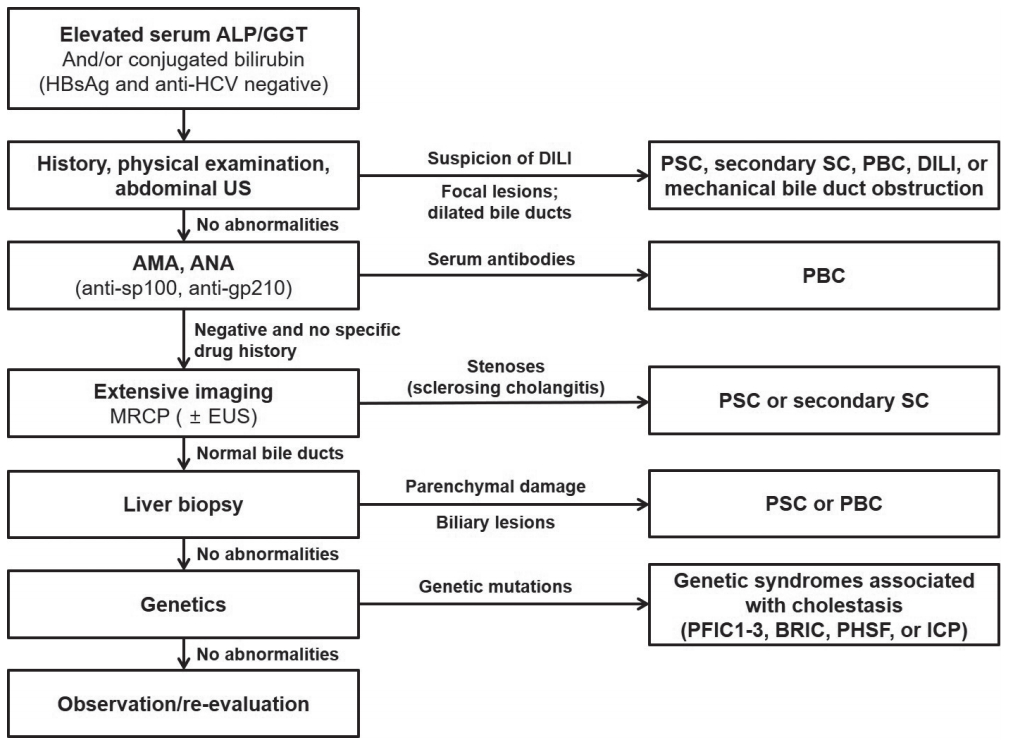

1. 만성 담즙 정체 시의 임상적 접근

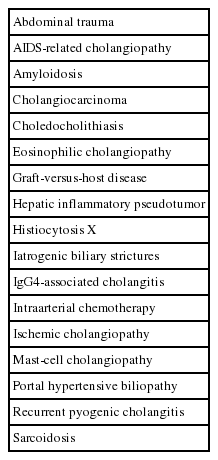

6개월 이상 지속되는 만성 담즙 정체(cholestasis)가 있을 경우, 감별 진단을 위한 접근 방법은 다음과 같이 정리할 수 있다(Fig. 1) [1]. 우선 약제 복용력을 확인하고 복부 초음파를 시행해서 약제로 인한 간 손상 또는 담관 폐색을 배제해야 한다. 약제로 인한 간 손상과 담관 폐색이 배제되면 anti-mitochondrial antibody와 anti-nuclear antibody (ANA)와 같은 혈청학적 검사를 시행해서 원발성 담즙성 담관염을 배제해야 하고, 이후 담췌관자기공명영상 (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, MRCP) 또는 내시경 초음파(endoscopic ultrasonography)를 시행해서 담관 협착 여부를 평가해서 경화성 담관염 여부를 확인해야 한다. 상기 검사 들에서 모두 특이 소견을 보이지 않으면 간조직 검사를 시행하고, 간조직 검사에서도 진단이 되지 않으면 유전자 변이 검사를 시행한다.

Algorithm of clinical, biochemical, and technical diagnostic measures in chronic cholestasis. In patients with cholestasis, a structured approach is recommended to reach a safe and secure diagnosis, facilitating prompt interventions as appropriate. ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase; US, ultrasonography; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; SC, sclerosing cholangitis; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; AMA, anti-mitochondrial antibody; ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; EUS, endoscopic ultraeonography; PFIC1-3, progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, type 1-3; BRIC, benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis; PHSF, persistent hepatocellular secretory failure; ICP, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.

2. 원발성 경화성 담관염

경화성 담관염은 담관의 미만성 염증과 섬유화로 인해 담관의 파괴와 협착이 진행하는 병적 상태를 의미하는 것으로 원발성 경화성 담관염(primary sclerosing cholangitis), 이차성 경화성 담관염(secondary sclerosing cholangitis) 그리고 immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) 관련 경화성 담관염(IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis)으로 구분된다[2]. 원발성 경화성 담관염은 원인 미상으로 발생하는 담즙 정제성 만성 간질환으로 지속적인 담관의 염증과 섬유화를 특징으로 한다[3,4].

1) 역학 및 통계

원발성 경화성 담관염 환자의 60%는 남성이며 진단 당시의 중간 연령은 41세로 알려져 있고, 발생률은 10만 명당 0-1.3건, 유병률은 10만 명당 0-16.2건으로 알려져 있다. 일본의 경우, 유병률이 10만 명당 0.95명으로 다소 낮은 것으로 알려져 있다. 북유럽에서의 연구 결과에 의하면 이러한 발생률과 유병률은 점차적으로 증가하는 것으로 알려져 있는데, 실제로 질병의 발생이 증가하는 것인지 아니면 MRCP 와 내시경역행담췌관조영술(endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, ERCP)의 시행 증가로 인해 진단 건수가 증가하는 것인지 여부는 아직 확실치가 않다. 2015년 일본에서 시행된 설문조사를 통한 연구에 의하면 진단 당시 연령대의 분포는 20-40대, 60-70대에서 peak를 보이는 것으로 보고되고 있다[2].

2) 발병 기전

원발성 경화성 담관염의 원인과 발병 기전에는 유전적 소인과 환경적 요인이 모두 관여하지만 유전적 소인의 역할은 10% 미만이고, 환경적 요인이 50% 이상의 역할을 하는 것으로 알려져 있다. 현재 주로 통용되고 있는 가설은 몇 가지의 유전적인 소인이 있는 환자에서 정체불명의 외부 환경요인에 노출될 경우, 장관(gut)에서 유리된 항원으로 인해 활성화된 T-cell들이 간과 담관으로 이동하게 되고, 이로 인한 면역 반응으로 인한 염증과 담즙 항상성(homeostasis)의 파괴로 인해 담즙 산으로 인한 담관벽 상피 세포의 손상이 발생하게 되고, 이로 인해 간성상세포(hepatic stellate cell)와 근섬유모세포(myofibroblast)가 활성화 되어 “onion skin fibrosis”라고 불리는 특징적인 섬유화로 진행하는 것으로 정리할 수 있다[5].

원발성 담관염 환자의 형제·자매에서의 발생률이 일반 인구에 비해 9-39배 높다는 것이 보고되면서 원발성 경화성 담관염의 발생에 유전적인 소인이 관여한다는 것을 확인할 수 있게 되었다[6]. 여러 전장유전체 연관 분석들의 결과에 의하면 원발성 경화성 담관염의 발생에 16개의 risk loci가 관련되고 있음이 알려져 있다. 6p21 염색체에 있는 HLA locus에 원발성 경화성 담관염의 발생과 관련된 부위가 위치하는 것으로 생각되고 있다. 원발성 경화성 담관염은 HLA class I, I, III 부위(HLA-B*08, HLA-DRB1 alleles, NOTCH4에 인접한 locus)와 강하게 연관이 있는 것으로 알려져 있다. 이러한 부위에서의 유전자 변이와 추정되는 항원 확인을 통해 새로운 치료의 target을 찾고자 하는 노력이 지속되고 있다.

또한, IL-2 pathway (CD 28, IL-2, IL-2 수용체의 a subunit)와 관련된 유전자가 원발성 경화성 담관염의 발생 위험을 증가시키는 것으로 알려져 있고, regulatory T-cell이 발병 기전에 중요한 역할을 하는 것으로 알려져 있다. 원발성 경화성 담관염 환자의 10%에서 혈청 IgG4 수치가 증가되어 있는 것으로 알려져 있지만, 원발성 경화성 담관염의 발병 기전에서의 B cell의 역할은 아직 확실치가 않다.

원발성 경화성 담관염의 발생에서 환경적 요인의 역할도 적지 않은 것으로 알려져 있다. 원발성 경화성 담관염 환자의 경우, 일반인에 비해 흡연량과 커피 소비량이 적은 것으로 알려져 있고 어렸을 때 가축에 노출되는 빈도가 높은 것으로 알려져 있다. 한 연구에 의하면 여성 환자의 경우, 여성 일반인에 비해 피임 호르몬 복용 빈도가 낮은 것으로 보고되었고[7] 다른 연구에서는 원발성 경화성 담관염이 있는 여성 환자의 경우, 일반인에 비해 요로감염 병력의 빈도가 높은 것으로 보고되었다[8]. 또한 이 연구에서는 원발성 경화성 담관염 환자의 경우, 일반인에 비해 생선의 섭취가 적고 육류와 햄버거의 섭취가 많은 것으로 보고하고 있어[8] 음식의 섭취와 조리 방법이 장내 미생물 군집에 영향을 미쳐 원발성 경화성 담관염의 발생에 영향을 미치는 것으로 생각되고 있다.

3) 진단 및 분류

원발성 경화성 담관염을 진단하기 위해서는 우선 경화성 담관염을 진단해야 하는데, 6개월 이상 지속되는 혈청 알칼리 포스파타아제(alkaline phosphatase, ALP) 수치의 상승, MRCP 또는 ERCP에서의 담관의 다발성 협착으로 경화성 담관염을 진단할 수 있다. 최근 가이드라인들에 의하면 경화성 담관염 진단의 일차적인 방법은 MRCP로 알려져 있다. 경화성 담관염으로 확인되면 다양한 원인으로 인한 이차성 경화성 담관염을 배제해야 하고(Table 1) [3], 이차성 경화성 담관염을 배제하면 원발성 경화성 담관염으로 진단할 수 있다. 원발성 경화성 담관염의 진단에서 간조직 검사가 필요한 경우는 MRCP 소견이 정상이지만 small duct subtype의 원발성 경화성 담관염이 의심되는 경우와 자가면역성 간염과의 병발이 의심되는 경우로, 이 경우를 제외하고는 원발성 경화성 담관염의 진단을 위해 간조직 검사가 반드시 필요하지는 않는 것으로 알려져 있다. 최근에는 간 섬유화 정도를 평가하기 위해 MR elastography 또는 transient elastography가 등장하여 시행되고 있지만, 원발성 경화성 담관염 환자에서의 진단적 역할은 아직 명확하지가 않다.

원발성 경화성 담관염의 경우는 여러 아형으로 구분할 수 있다(Table 2) [3]. Classic subtype은 전체 담관을 침범한 경우로 전체 원발성 경화성 담관염의 90%를 구성하고 있다. 원발성 경화성 담관염의 5%는 작은 간내 담관만 침범한 small duct subtype이다. 원발성 경화성 담관염과 자가면역성 간염이 병발하는 overlap syndrome은 소아 원발성 경화성 담관염의 35%를 차지하지만 성인 원발성 담관염에서는 5% 정도로 알려져 있다. 아형에 따라 임상 양상과 병의 진행이 다른 것으로 알려져 있는데, 일반적으로 small duct subtype의 경우는 classic subtype에 비해 예후가 좋은 것으로 알려져 있다.

원발성 경화성 담관염 환자의 10%에서 혈청 IgG4 수치가 상승되어 있는데, 이 경우 예후가 보다 좋지 않은 것으로 알려져 있다. 이러한 IgG4 수치의 상승이 동반된 원발성 경화성 담관염의 경우 반드시 IgG4 관련 경화성 담관염이 아닌지를 감별하는 것이 중요하다. 원발성 경화성 담관염과는 달리 IgG4 관련 경화성 담관염의 경우 스테로이드 치료에 임상적 효과가 좋은 것으로 알려져 있어 감별이 특히 중요하다. IgG4 관련 경화성 담관염의 경우, 원발성 경화성 담관염에 비해 췌장의 종괴 또는 췌관의 협착이 동반되어 있는 경우가 흔하고 담관 협착 부위의 길이가 비교적 길다는 특징이 있다. 또한, IgG4 관련 경화성 담관염의 경우, 발생 부위(담관 또는 췌장)의 조직 소견 상 IgG4 양성 lymphoplasmacyte의 침윤 소견, 갑작스럽게 발생하는 황달, 스테로이드 치료 후 담관 협착이 호전된다는 특징과 염증성 장질환이 동반되지 않는 특징이 있다.

4) 임상 양상 및 예후

원발성 경화성 담관염은 서서히 진행되는 임상 경과를 보여, 50%에서는 진단 당시 증상이 없이 간수치 상승 소견만 있는 것으로 알려져 있다. 원발성 경화성 담관염의 자연 경과를 보면 간과 관련된 증상과 간기능 검사 소견은 fluctuation이 매우 심한 것으로 알려져 있고, 동반된 염증성 장질환의 활성도와는 관련이 없는 것으로 알려져 있다. 환자들마다 매우 다양한 자연 경과를 보이지만, 거의 모든 환자에서 결국에는 비대상성 간경변증으로 진행해서 간이식을 고려해야 하는 것으로 알려져 있다. 간이식까지의 기간은 일반 인구에서의 연구와 간이식센터에서의 연구에서 결과에 차이가 있지만 진단 후 10-22년 정도로 알려져 있고, small duct type의 경우는 classical large duct type에 비해 간이식까지의 기간도 길고 예후가 양호한 것으로 알려져 있다[5].

일반적으로 원발성 경화성 담관염은 서서히 진행하므로 다양한 예후를 보이는 것으로 알려져 있다. 네덜란드의 44개 기관에서 시행한 대규모 연구 결과, 원발성 경화성 담관염 환자들의 생존 기간은 약 21.3년 정도이고, 이식센터만을 대상으로 분석할 경우는 13.2년으로 보고되었다[9]. 일본에서 시행된 한 전국적인 조사 결과 5년, 10년 생존율은 각각 81.3%, 69.6%였고, 5년, 10년 내 간이식을 하지 않을 확률은 77.4%, 54.9%로 보고되었다[10].

원발성 경화성 담관염의 진행 속도를 예측 가능한, 신뢰할 수 있는 지표는 아직 없는 것으로 알려져 있다. 원발성 담즙성 담관염의 경우 치료 중의 ALP, bilirubin 수치의 변화가 예후를 평가하는 데 도움이 되어 임상에서 크게 활용되고 있지만, 원발성 경화성 담관염에서는 도중에 급성 세균성 담관염 등의 발생 등으로 워낙 fluctuation이 심해서 ALP 수치가 원발성 경화성 담관염의 장기 예후를 예측하고 임상 연구의 결과 지표로 사용되기에는 아직 근거가 부족한 상태이다.

원발성 경화성 담관염 환자의 6%는 세균성 담관염으로 처음 증상이 발현되는 것으로 알려져 있는데, 이러한 세균성 담관염은 진단 후에도 반복적으로 발생할 수 있으며, 이 경우 간이식을 필요로 하는 경우도 있다. 독일에서 시행된 한 코호트 연구에서는 273명의 환자들을 평균 76개월 동안 추적 관찰을 시행한 결과, 40%의 환자에서 dominant stricture (간외담관이 1.5 mm 이하로 협착 또는 간내담관 분지 부위의 2 cm 이내 부위가 1 mm 이하로 협착)가 발생하였고 15-20%의 환자에서 담관암 동반이 의심되는 것으로 보고되었다[11]. 따라서 이러한 dominant stricture가 있는 경우, 담관암 동반 여부를 감별하기 위한 적극적인 검사가 필요하다.

원발성 경화성 담관염의 경우, 거의 대부분에서 염증성 장질환(궤양성 대장염, 크론병)이 동반되어 있는 것으로 알려져 있어 원발성 경화성 담관염으로 진단된 모든 환자에서 대장내시경을 시행하는 것이 권고된다. 한 연구에 의하면 원발성 경화성 담관염과 염증성 장질환이 함께 있는 모든 환자에서 거의 전체 대장에 걸쳐 염증성 장질환이 있었고, 일부에서는 회장 말단 부위에도 염증이 동반되어 있는 것으로 보고되었다[12]. 원발성 경화성 담관염과 염증성 장질환이 함께 있을 경우, 염증성 장질환만 있는 경우에 비해 대장암의 발생 위험이 4배로 증가하는 것으로 알려져 있고 일반인에 비해서는 10배인 것으로 알려져 있다.

원발성 경화성 담관염에서는 다양한 담낭 질환이 동반되는 경우가 많은데, 25%에서 담낭 결석, 6-14%에서 담낭 종괴가 동반되는 것으로 보고되고 있으며, 담낭 종괴의 60%는 담낭 선암인 것으로 보고되고 있다. 한 연구에서는 원발성 경화성 담관염 환자들에 대해 간이식 전 또는 간이식과 함께 담낭절제술을 한 경우 37%에서 담낭 이형성이 진단되고, 14%에서 담낭 선암이 진단된 것으로 보고되었다[13].

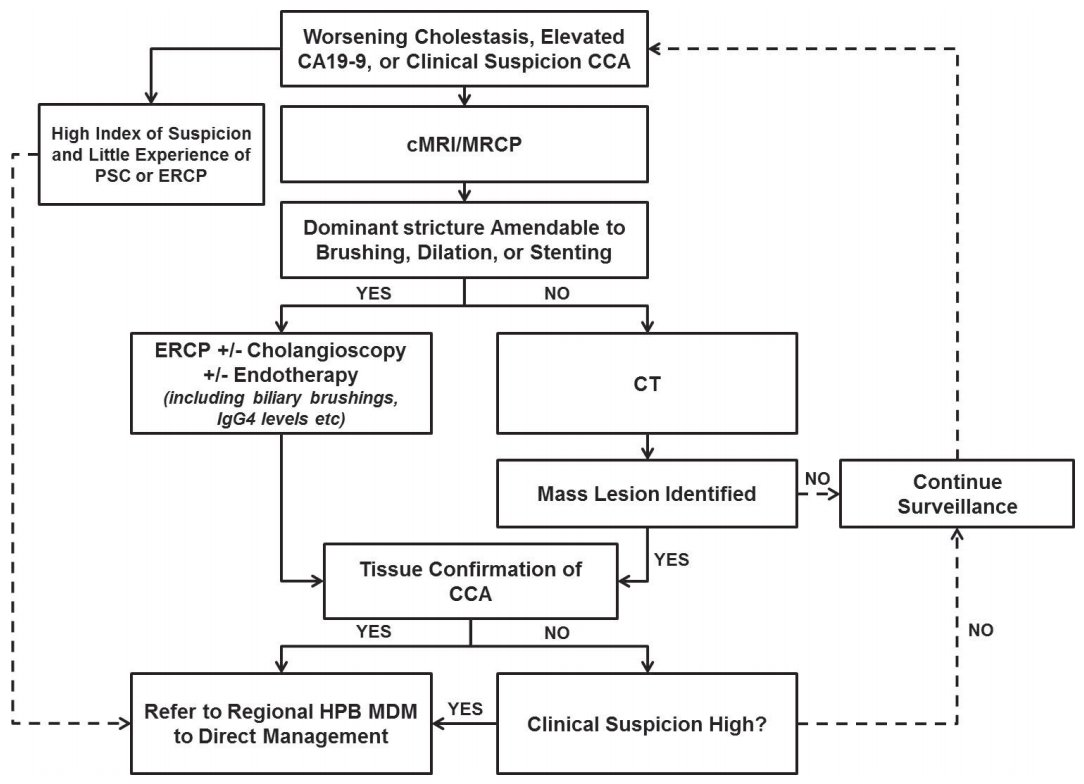

원발성 경화성 담관염에서는 담관암의 위험이 크게 증가하여 일반인의 400배 정도로 알려져 있고 선진국에서는 담관암의 가장 흔한 위험인자로 알려져 있으며, 원발성 경화성 담관염 환자의 사망 원인 중 가장 흔한 원인으로 알려져 있다. 담관암으로 진단되는 경우 중 절반 정도는 원발성 경화성 담관염 진단 후 1년 내에 진단되는 것으로 알려져 있고, 이후 incidence는 1년에 0.6-1.5%이고, lifetime risk는 20%로 알려져 있다[4]. 따라서 원발성 경화성 담관염에 대한 추적 관찰 중 황달, 발열, 체중 감소 등의 증상이 새로이 나타나거나 간수치 또는 종양표지자 수치의 변화가 있을 경우, 담관암 발생 가능성을 염두해두고 복부 전산화단층촬영(computed tomography, CT), MRCP, ERCP 등의 적극적인 검사를 시행하는 것이 필요하다.

5) 치료 및 추적 관찰

현재까지 원발성 경화성 담관염에 대한 간이식 전 예후를 개선시키는 것으로 입증된 약물 치료는 아직 없는 실정이다. 원발성 경화성 담관염 환자들에 대해 우르소데옥시콜산(ursodeoxycholic acid, UDCA) 투여가 시행되고 있지만, 많은 임상시험에서 UDCA 복용이 예후를 개선시키는 결과를 보이지 못하고 있고, 고용량 투여(>28 mg/kg/day) 시에는 오히려 예후를 악화시킨다는 보고도 있다. 따라서 American Association for the Study of Liver와 American College of Gastroenterology에서의 임상 권고안에서는 원발성 경화성 담관염에 대한 치료로 UDCA 투여를 권고하지 않고 있다[14,15]. 하지만 일부 후향적 코호트 연구들에서 UDCA 투여 시작 6개월, 1년 후 혈청 ALP 수치가 감소할 경우, 장기적인 예후의 개선과 관련이 있다는 보고들이 있어 European Association for the Study of the Liver에서의 임상 권고안에서는 적정 용량(13-15 mg/kg)의 UDCA 투여를 권고하고 있다[16].

원발성 경화성 담관염에서는 ERCP를 통한 중재 시술이 필요한 경우가 있는데, dominant stricture (간외담관이 1.5 mm 이하로 협착 또는 간내담관 분지 부위의 2 cm 이내 부위가 1 mm 이하로 협착)가 있으면서 급성 담관염이 동반되어 있는 경우와 담관암 발생이 의심되어 조직 진단이 필요한 경우, 담관 담석이 동반되어 있는 경우가 ERCP의 적응증이 된다[4,17].

원발성 경화성 담관염에서 ERCP를 시행하게 될 경우, 예방적 항생제를 사용할 것과 ERCP 전에 MRCP를 통한 평가를 먼저 시행할 것이 권고되고 있다[18]. 그리고 dominant stricture가 있을 경우, 담관암 여부를 확인하기 위해 반드시 조직 진단을 시행할 것이 권고되고 있다[18]. Dominant stricture에 대한 담관 배액을 위해 풍선확장술과 스텐트 삽입술 중 어떤 것을 시행할지와 스텐트 종류와 삽입 기간에 대해서는 가이드라인들과 연구들에 따라 권고 내용에 차이가 있는 상태이다.

원발성 경화성 담관염에 대한 궁극적인 치료는 간이식으로, 북유럽에서는 원발성 경화성 담관염이 간이식의 적응증의 15% 정도를 차지하는 것으로 알려져 있다[5]. 유럽 간이식 레지스트리를 통한 연구에 의하면 원발성 경화성 담관염에 대한 간이식 후 1년, 3년, 5년 생존율은 각각 86%, 80%, 77%로 원발성 담즙성 담관염에 비해 예후가 좋지 않은 것으로 알려져 있다[4]. 간이식 전에 동반된 염증성 장질환에 대해 장절제술을 시행해야 할지에 대해서는 연구들에 따라 권고 내용에 차이가 있고, 간이식 후에도 10-40%에서 원발성 경화성 담관염이 재발할 수 있는 것으로 알려져 있다.

원발성 경화성 담관염에서는 대부분의 환자에서 간경변증으로 진행하고 담관암과 대장암의 발생 위험이 크게 증가하므로, 이에 대한 정기적인 추적 관찰이 권고된다. 아직 입증된 추적 관찰 방법이 정립되어 있지는 않지만 6개월-1년마다 초음파 또는 MRCP를 통한 추적 관찰이 권고되고 있고, 간경변증이 발생할 경우 6개월 간격의 추적 관찰이 권고되고 있다[5]. 또한, 염증성 장질환이 동반될 경우 1년마다 대장내시경을 시행할 것이 권고되고 있다[4]. 추적 관찰 중 담관암 발생이 의심될 경우 MRCP와 CT, 필요 시 ERCP 또는 cholangioscopy 등을 통한 조직 진단을 통한 적극적인 검사를 시행할 것이 권고되고 있다(Fig. 2) [4].

Algorithm for the investigation of possible cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; CT, computed tomography; HPB MDM, hepato-pancreato-biliary multidisciplinary meeting.

2. 원발성 담즙성 담관염

원발성 담즙성 담관염(primary biliary cholangitis)은 간에서 발생하는 자가면역 질환으로, 서서히 그리고 지속적으로 진행되는 간내 작은 담관의 파괴로 인해 답즙과 여러 독성물질들이 간에 축적되어 담즙 정체(cholastatis) 상태를 보이게 되고, 결국 이로 인해 간세포 파괴 및 섬유화, 궁극적으로는 간경변증으로 진행하게 되는 질환이다. 1851년에 처음 발견되고 1949년에 원발성 담즙성 간경변증(primary biliary cirrhosis)으로 불렸으나, 간경변증은 질환이 진행되었을 경우에만 나타나므로 2014년부터는 원발성 담즙성 담관염으로 명명하게 되었다. 주로 여성에서 발생하고 (여성/남성 비율 9:1), 유병률은 다양해서 100만 명당 40-400건, 일본에서는 100만 명당 27-54건으로 알려져 있다.

1) 진단

원발성 담즙성 담관염의 진단은 담즙 정체 증상이 있는 경우, 다른 원인을 배제한 상태에서 ALP, 감마 글루타밀 펩티드 전이효소(gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase) 수치의 상승과 혈청 AMA 또는 anti-sp100, anti-gp201의 양성 소견으로 진단할 수 있다. AMA는 1965년 원발성 담즙성 담관염 환자에서 처음 측정된 이래 원발성 담즙성 담관염의 진전에 가장 중요한 혈청학적 검사이다. 원발성 담즙성 담관염 환자의 95%에서 AMA 양성인 것으로 알려져 있지만 일반인에서도 1% 정도에서는 검출되는 것으로 알려져 있다. 임상적으로 원발성 담즙성 담관염이 의심되지만 혈청학적 소견이 음성이면 간조직 검사가 필수적인데, 간조직 검사 상 “florid ductal lesion”이라고 불리는 비화농성 담관염 및 소엽간 담관의 파괴 소견이 특징적 소견이다[1]. 간섬유화 정도에 따라 4단계로 구분되어 치료 효과와 예후를 평가하는 데 활용될 수 있다. 특징적인 혈액 검사 소견과 AMA 양성 소견을 보이는 경우 진단을 위해 간조직 검사가 반드시 필요하지는 않지만 원발성 담즙성 담관염의 진행 단계를 확인하거나 자가면역성 감염과 병발하는 overlap syndrome을 배제하기 위해서 그리고 임상적으로 의심되나 AMA 음성일 경우에는 간조직 검사가 반드시 필요하다. 특히 overlap syndrome의 경우, 임상 경과의 호전을 위해 스테로이드의 치료가 필요하므로 감별이 중요한데(Table 3) [19,20], 이를 위해 간조직 검사가 필요한 경우가 많다.

2) 임상 양상 및 위험도 평가

원발성 담즙성 담관염은 진단 당시 대부분 증상이 없지만 10년 후에는 50%에서 증상이 발생하는 것으로 알려져 있다. 진단 당시 가장 흔한 증상은 피로감과 소양증이다. 피로감은 원발성 담즙성 담관염 환자의 78%에서 보이는 것으로 알려져 있고 질병의 중증도, 조직학적 병기, 질병의 이환 기간과는 관련이 없는 것으로 알려져 있지만 환자의 삶의 질을 크게 저하시킬 수 있는 주된 원인이다. 소양증은 20-70%에서 발생하는 증상으로 원발성 담즙성 담관염 환자가 가장 힘들어하는 증상 중 하나이다. 보통 황달이 발생하기 수개월-수년 전에 발생하고 천에 닿거나 열과 접촉 시 악화되는 것으로 알려져 있다. 우상 복부 불편감이 10%에서 나타나고 고지혈증, 갑상선기능저하증, 골감소증 또는 Sjogren 증후군이나 scleroderma와 같은 자가면역 질환과 동반될 수 있는 것으로 알려져 있다.

UDCA 치료의 효과가 입증되어 널리 시행되면서 예후가 크게 개선되었지만 일반인에 비해서는 예후가 좋지 않으며, 원발성 경화성 담관염과 마찬가지로 자연 경과가 개개인의 환자들마다 매우 다양한 것으로 알려져 있어 지속적인 추적 관찰과 추후 비대상성 간경변증으로의 진행에 대한 위험도 평가가 필요하다.

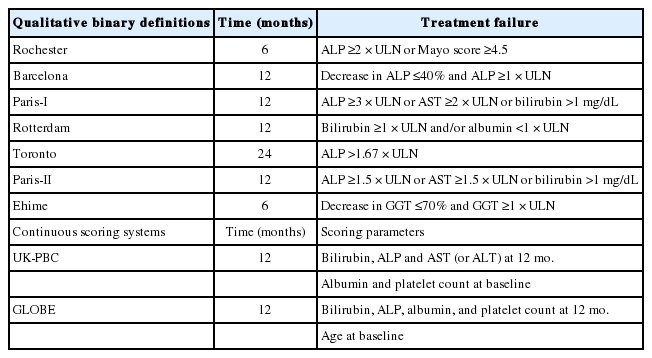

실제로 1차 치료로 시행되는 UDCA 치료 후에도 치료 반응(response)이 충분치 않은 경우가 25% 정도로 이 경우 비대상성 간경변증으로의 진행 위험이 높은 것으로 알려져 있어 원발성 담즙성 담관염 환자에 대한 위험도 평가 중 가장 중요한 것 중 하나가 UDCA에 대한 response를 평가하는 것이라 할 수 있다. 여러 가지 지표들이 있지만 transient elastography를 통한 간 탄성도(liver stiffness) 측정과 ALP, bilirubin과 같은 간기능 검사지표가 가장 많이 사용되고 있다. 현재까지 여러 연구들을 통해 ALP와 bilirubin과 같은 혈액 검사를 통해 UDCA 치료의 response 평가를 평가하는 수많은 방법들이 개발되어 왔고 임상에서 활용되고 있는데, 대부분의 경우 UDCA 치료 후 12개월에 response를 평가해서 위험도를 평가하도록 되어있다(Table 4) [1,21-29]. Continuous scoring system인 GLOBE scoring system과 UK-PBC scoring system의 경우, 각각 http://www.globalpbc.com/globe와 http://www.uk-pbc.com에서 환자의 혈액 검사 소견을 입력하면 위험도를 평가할 수 있다.

European Association for the Study of the Liver에서의 권고안에서는 원발성 담즙성 담관염으로 진단된 모든 환자에서 진단 시 ALP, bilirubin, albumin, platelet count 및 elastography를 시행할 것을 권고하고 있고, UDCA 치료 후 elastography와 GLOBE score 또는 UK-PBC score 등의 risk scoring system을 통해 비대상성 간경변증으로의 진행 위험을 평가할 것을 권고하고 있다[1]. 또한 UDCA 치료 12개월 후 ALP 수치가 정상 상한선의 1.5배 미만이면서 bilirubin 수치가 정상인 환자의 경우에는 이식 전 생존 기간(transplant-free survival)이 일반인과 차이가 없음을 제시하고 있다[1].

3) 치료

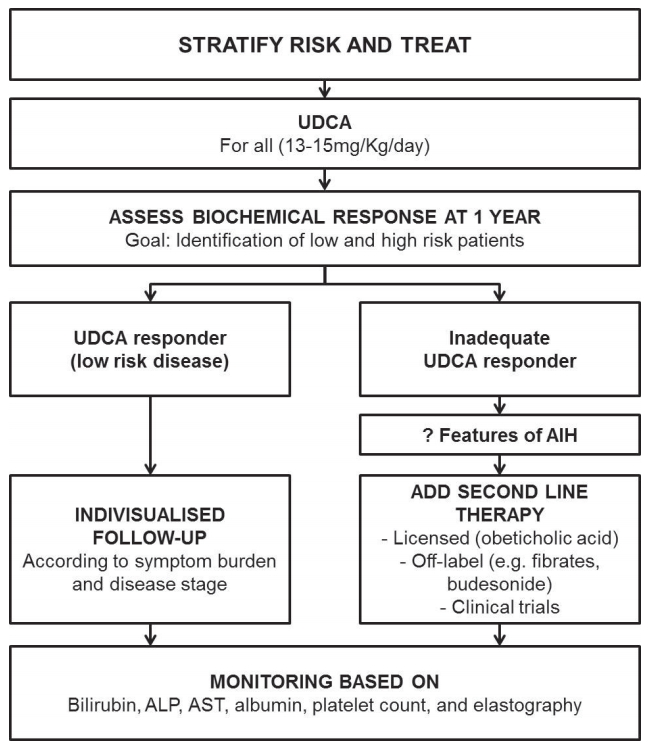

원발성 담즙성 담관염의 치료는 크게 1) 질병의 경과를 늦추기 위한 약물 치료, 2) 간경변증 단계 평가 및 치료, 3) 증상에 대한 대증 치료로 구성되어 있다. 이 중 질병의 경과를 늦추기 위한 약물 치료 시행 시에는 치료 12개월 후 response에 대한 평가가 필요하고 이에 따라 치료 방침이 달라지게 된다(Fig. 3) [1].

EASL clinical guideline in primary biliary cholangitis consensus management flow chart. In patients with primary biliary cholangitis, a struc tured approach to their life-long care is impor tant and recommended. UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

원발성 담즙성 담관염의 경과를 늦추어 예후를 개선시킬 수 있는 약물 치료에 대한 많은 연구들이 있었는데, 임상적 효과가 입증되어 임상에서 사용이 승인된 약제로는 UDCA와 obeticholic acid가 있고, 아직 임상 연구 중인 약제로는 budesonide와 fibrate 제제가 있다.

많은 연구들에서 UDCA 투여 시 생화학지표가 호전된다는 것은 알려져 있고 3개의 무작위 연구에 대한 combined analysis 결과[30]와 Global PBC Study Group에서 시행한 메타분석 결과[31] UDCA 치료를 한 group에서 transplant-free survival이 개선되는 것으로 보고되면서 UDCA는 현재 모든 가이드라인에서 1차 치료로 권고되고 있고, 진단 후 평생 복용할 것이 권고되고 있다(13-15 mg/kg/day). 임신 또는 수유 중에서의 안전성에 대해서는 data가 충분하지는 않지만 risk와 benefit을 고려하면 투여를 지속할 수 있는 것으로 권고되고 있다.

원발성 담즙성 담관염에서 UDCA 치료가 response가 없는 경우가 있고, 이 경우 예후가 좋지 않은 것으로 알려져 있어 새로운 기전의 약제에 대한 연구가 지속되고 있다. UDCA의 기전이 주로 post-transcriptional mechanism이라면 그보다 upstream level인 nuclear receptor 또는 membrane receptor를 target으로 하는 agonist에 대한 여러 임상 연구들이 진행 중에 있다[32]. 그중 obeticholic acid는 FXR receptor의 agonist로 3상 연구에서 ALP와 bilirubin 수치 개선과 같은 생화학지표의 개선이 있음이 입증되어[33] UDCA 치료에 response가 없을 경우, UDCA와의 병합 요법 또는 단독 요법으로 사용할 수 있는 것으로 승인이 되었고 survival benefit에 대한 평가를 위해 장기간의 무작위 연구가 진행 중이다.

원발성 담즙성 담관염에서도 비대상성 간경변증으로 진행할 경우 간이식이 필요하다. 원발성 담즙성 담관염의 유병률이 증가하는 추세임에도 불구하고 간이식의 적응증으로 원발성 담즙성 담관염이 차지하는 비율은 수십 년간 감소 추세에 있다[34-36]. 원발성 담즙성 담관염의 경우, 간이식 후 5년 생존율이 80-85%로 다른 만성 간질환에 비해 간이식 후 예후가 좋은 것으로 알려져 있다[34-36]. 간이식 10년 후 20-25%에서 원발성 담즙성 담관염이 재발하지만, 이는 생존 기간에는 크게 영향을 미치지 않는 것으로 알려져 있다[37].

결 론

원발성 경화성 담관염과 원발성 담즙성 담관염은 임상에서 흔히 접하지는 않지만 원인 미상의 담관 폐색이나 담즙 정체가 발생할 경우, 반드시 의심하고 감별을 해야 할 질환이다. 특히 치료 방침과 예후가 크게 달라지므로 자가면역성 간염과 이차성 경화성 담관염, IgG4 관련 경화성 담관염과의 정확한 감별은 필수적이다. 원발성 경화성 담관염과 원발성 담즙성 담관염의 장기적인 예후는 아직 만족스럽지 않은 상태로 추후 발병 기전에 대한 보다 정확한 이해와 새로운 약제의 개발이 필요할 것으로 생각되고, 국내의 원발성 경화성 담관염과 원발성 담즙성 담관염의 역학과 임상 양상, 치료와 예후에 대한 학회 차원에서의 정확한 평가도 필요할 것으로 생각된다.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflicts to disclose.