간전이가 있는 췌장신경내분비종양의 인터벤션 치료

Liver Directed Interventional Treatments for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor with Liver Metastasis

Article information

Abstract

췌장신경내분비종양(PNET)은 드물지만 최근 진단 기술의 발전으로 발견 빈도는 증가하고 있다. PNET의 간전이는 장기 생존과 상관 관계가 높아서 이에 대한 적극적인 치료가 중요하다. 간 전이가 있는 PNET 환자에서 약물 치료에도 불응하는 증상이 있거나 무증상이지만 약물 치료에도 진행하는 절제 불가능한 간전이가 있을 때 간직접 치료를 추천하고 있다. 국소 소작술, 간동맥 색전술(TAE), 간동맥화학색전술(TACE), 간동맥 방사선 색전술(TARE) 등을 포함하는 간직접 인터벤션 치료는 증상을 호전시키고 생존율을 향상시키는 중요한 역할을 담당하고 있다. 본고의 목적은 PNET의 간전이를 치료하기 위한 간직접 인터벤션 치료의 최신 지견에 대해 기술하는 것이다.

Trans Abstract

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are rare, but the frequency of detection is constantly increasing due to recent advances in diagnostic technology. Since liver metastasis (LM) of PNETs is highly correlated with long-term survival, active treatment is important. Liver-directed treatment is recommended for patients with unresectable LM from PNET if symptomatic or progressing despite medical management. Liverdirected intervention treatment, including locally ablative techniques and hepatic arterial embolotherapy has a vital role in controlling symptoms and improving overall survival rates. The purpose of this article is to address the recent advances in liverdirected intervention treatments for the treatment of LM of PNETs.

서 론

췌장신경내분비종양(pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, PNET)은 드문 종양으로 모든 췌장 종양의 1.3-10.0% 비율을 차지한다. 최근에 진단 기술의 발전과 함께 발견 빈도는 증가하고 있는 추세이다[1]. 기능성 종양과 비기능성 종양으로 분류되는데, 비기능성 종양은 특이 증상이 없어 대개 진단이 늦어지는 경우가 많다. PNET 환자의 40-80%는 진단 당시에 전이가 존재하며, 그중 가장 흔한 부위는 간(40-93%)이다[2]. 간전이는 예후에 부정적 영향을 끼치며 간전이의 정도는 장기 생존과 상관 관계가 있다[3,4]. 간전이의 발생은 종양의 조직학적 형태, 원발 종양 위치와 연관이 많다[4,5]. 또한 예후에 강한 영향을 미치는 다른 요소들은 원발 종양의 크기, 세포분열지수(mitotic index), 혈관과 림프관 침범, 증식 활성도(proliferative activity), 혈중 대사물질 농도, 세포의 비정형(cellular atypias) 등이 있다[4,5].

PNET의 간 전이에 대한 치료의 목적은 국소 종양 조절과 증상 완화에 있다[6]. 간전이가 있는 PNET 환자에서 약물치료에도 불응하는 증상이 있거나 무증상이지만 약물 치료에도 진행하는 절제 불가능한 간전이가 있을 때 간 직접 치료(liver-directed therapy)를 추천하고 있다[7]. 소작술, 간동맥 색전술(transarterial embolization, TAE), 간동맥화학색전술(transarterial chemoembolization, TACE), 간동맥 방사선 색전술(transarterial radioembolization, TARE) 등을 포함하는 인터벤션 간 직접 치료는 증상을 호전시키고 전체 생존율(overall survival, OS)을 향상시키는 중요한 역할을 담당하고 있다[6-8]. 하지만 어느 치료 기법이 최적의 치료 기법인가에 대해서는 아직 논란이 많고 추가적인 연구가 필요하다. 본고에서는 PNET의 간전이를 치료하기 위한 인터벤션 치료의 최신 지견에 대해 기술하고자 한다.

본 론

PNET의 간전이의 예후는 대개 간실질 침범 정도와 간실질이 종양 조직으로 대체되어 생기는 간세포 부전에 따라 달라진다[9]. 하나 혹은 소수의 간전이 환자는 수술이나 국소 소작술과 같은 완치술이 필요하나 다수의, 양측성, 절제 불가능한 간전이 환자는 증상, 생물학적 이상, 환자의 삶의 질 그리고 무진행 생존율(progression-free survival)을 향상시키기 위해 종양의 부피와 내분비(endocrine secretion)를 줄이는 완화 치료가 중요하다[9]. 2005년 Touzios 등[10]에 의하면 PNET의 간전이를 적극적으로 치료하지 않은 군에서는 5년 생존율이 20%, 중앙 생존 기간이 20개월이었지만, 적극적으로 치료한 군에서는 간절제술과 소작술을 함께 시행하였을 때 5년 생존율이 72%, 중앙 생존 기간이 96개월 초과였고, TACE를 시행하였을 때는 5년 생존율이 50%, 중앙 생존 기간이 50개월이었다. 즉, 적극적으로 치료한 군에서 적극적으로 치료하지 않은 군보다 통계적으로 유의하게 더 나은 생존율을 보였다(p <0.05).

1. PNET의 인터벤션 치료

1) 국소 소작술(locally ablative technique)

PNET의 간전이의 국소 소작술에는 고열을 이용해 응고 괴사를 유도하는 고주파 열치료(radiofrequency ablation, RFA)와 극초단파 열치료(microwave ablation, MWA)와 같은 열소작술(thermal ablation), 종양괴사를 유발하기 위해 반복적 급속냉동을 가하는 냉동소작술(cryoablation), 에탄올 같은 화학약품을 이용한 에탄올 주입술(percutaneous ethanol injection) 등이 있다.

(1) RFA

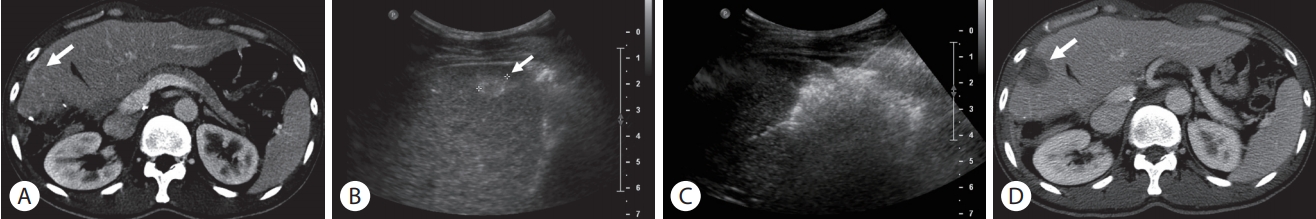

RFA는 간 종괴에 17 gauge 혹은 15 gauge 전극을 삽입한 뒤 고주파 전류(약 480 kHz)를 가하여 조직 내 이온들의 진동을 유도해 마찰열을 만들어 종양 내 온도를 상승시켜 종양을 응고 괴사 시키는 방법이다[11]. RFA는 초음파나 컴퓨터단층촬영(computed tomography, CT) 영상 유도 하에 경피적으로 시행하거나 수술중 시행될 수 있다(Fig. 1).

Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for the treatment of a recurrent metastatic nodule after right hepatectomy due to pancreas neuroendocrine tumor. (A) On contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) image, there is a 1.2-cm low attenuation nodule (arrow) in hepatic segment IV. (B) The recurrent metastatic nodule (arrow) is hyperechoic on ultrasonographic image. (C) The nodule was successfully treated with percutaneous RFA. (D) Portal phase CT image obtained immediately after RFA shows ablation zone (arrow).

PNET의 RFA는 주로 수술적 절제와 부속 치료(adjunctive treatment)로 시행될 수 있고, 특히 간 실질 손상을 최소화하기 위해 깊은 위치의 작은 병변의 치료에 장점이 있다. 또한 절제 불가능한 환자의 증상 완화, 수술 또는 이전 RFA 후 재발한 경우에 고려할 수 있다. 대개 단발성 종양은 장경 5 cm 이하, 다발성 종양은 3개 이하이고, 장경이 3 cm 이하인 경우에 기술적으로 시행 가능하다[12].

그러나 RFA는 소작 범위에 제한이 있어 종양의 장경이 3 cm 이상인 종양의 경우 국소 재발률이 높고, 혈관 주위 종양의 치료 시 각각 열씻김 현상(heat sink effect)으로 치료 효과가 낮고, 담도와 접한 경우 담도 손상으로 인한 협착 가능성이 높다는 단점들이 있다[11,13]. 또한 4개 이하의 소수의 결정성 간전이 치료에 국한될 수 있어서 주로 다발성 간전이로 발현되는 신경내분비종양의 치료에는 제한이 있을 수 있다[14]. 따라서 적절한 치료 대상을 선택하는 것이 중요하고, 생존율과 증상을 향상시키는 용적 축소 수술(debulking surgery)의 경험에 기초하여 90%이상의 종양 부하를 파괴하는 적극적 소작술이 현재 권장된다[12].

RFA의 3년 OS는 84%[15], 5년 생존율은 53%[2]로 보고되고 있다. Akyildiz 등[16]은 1.3년의 중앙 무질병 생존 기간(median disease-free survival)과 6년의 OS를 보고하였고, 국소 재발은 7.9%에서 보였지만 새로운 종양이 63%에서 발생하였다. 증상은 97%에서 향상되었다. 이환율은 6%, 30일 사망률은 1%로 낮았다. RFA의 주요 합병증은 문맥 혈전증, 혈복강, 대장 천공, 간농양, 종양 파종(tumor seeding)이었고, 경미한 합병증은 통증, 간 분절담도 확장, 흉수, 간 피막하 혈종(hepatic subcapsular hematoma)이었다[16,17].

(2) MWA

MWA는 간 종괴 내에 위치한 전극침에서 전자스펙트럼(electromagnetic spectrum)의 일종인 극초단파(microwave)를 방출하여 조직의 응고 괴사를 유도하는 치료 방법이다. 조직 내 물분자를 포함하는 극성물질(양전하 또는 음전하를 띄는 물질)이 극초단파의 영향을 받아 전장의 방향이 매 초당 24억 5천만 번씩 변하게 되고 이 극성물질들이 서로 충돌하게 되어 조직 내에 마찰열이 발생한다. 이때 발생한 열에 의해 종양의 응고 괴사가 일어난다[18].

Martin 등[18]에 의한 전향적 연구는 11명의 신경내분비종양 간전이 환자를 포함하는 결과를 보고하였는데, 완전 관해율(complete response)이 90%, 국소 재발율은 0%였다. 이환율 및 사망률은 각각 29%와 0%였다. 최근의 Perrodin 등[19]에 의한 후향적 연구에서 MWA는 신경내분비종양 간전이 환자의 치료에 있어 수술적 절제와 유사하게 우수하고 안전한 치료법이라 보고하였다. 2008년부터 2017년까지의 간전이가 있는 신경내분비종양 환자 47명에서 시행받은 68예의 치료를 대상으로 하였는데, 수술적 절제 34예, MWA 20예, 복합 치료 14예를 분석하였다. MWA군과 수술적 절제군 사이에 국소 재발률의 차이가 없었다. MWA만 시행한 군과 MWA를 시행받거나 받지 않은 수술적 절제군 사이에 평균 생존율도 차이가 없었다(p =0.1570). MWA 후에 주요 합병증은 발생하지 않았다.

(3) 기타 국소 소작술

냉동소작술(cryoablation)과 경피적 에탄올 주입술(percutaneous ethanol injection)은 주요 구조물 또는 혈관 근처에 종양이 위치하는 경우에 시행될 수 있는 대체될 수 있는 치료법이다. 냉동소작술은 간 종괴 내에 냉동탐침(cryoprobe)을 삽입하여 교대로 일어나는 냉동(freezing)과 해빙(thawing)을 통해 냉동탐침 주변 조직에 얼음구(iceball)가 형성되고 조직 괴사를 유도하는 치료법이다[20,21]. 시술 시작 3분 내 영하 20도로 감소시키고, 최대 영하 40도까지 온도를 낮출 수 있다. 영하 19.4도 이하로 온도가 감소하면, 세포 안에 얼음 결정체가 생겨 세포막을 파괴시키고 세포사멸(apoptosis)이 일어나고, 세포 밖의 얼음 결정체는 세포로의 수분 공급을 차단시켜 삼투압 이상을 초래한다. 냉동 후의 해빙은 세포의 부종과 사멸을 유도한다[22]. 완전한 소작을 위해 현재는 2회 순환의 냉동-해빙이 권장된다[20]. 얼음구로부터 거리가 멀어질수록 냉동 효과가 감소하기 때문에 종양 주변 5-10 mm 정도까지 충분히 냉동시켜야 완전한 소작을 기대할 수 있다[20]. 고주파 소작술에 비하여 주변 장기의 손상이 적고 주변 혈관에 의한 열씻김 현상 역시 적은 것으로 보고되어 있다. 시술하는 동안 초음파 또는 CT 영상을 통해 소작되는 병변의 경계를 쉽게 확인할 수 있다[20]. Bilchik 등[21]은 치료에 불응하는 유증상 신경내분비종양의 간전이 환자에서 냉동소작술이 유용한 치료법이라 보고 하였다. 냉동소작술 후에 종양 표지자가 80-90%까지 감소하였고, 국소 재발율은 20% 미만이었다. 중앙 무증상 생존율은 10개월, OS는 49개월 초과였다.

경피적 에탄올 주입술은 종양 내에 에탄올을 주입하여 화학적 조직 파괴를 유도하는 치료법이다. 이 치료법은 주로 간암 치료에 이용되어 왔으나 신경내분비종양 간전이에서도 적용될 수 있다[23-25]. Livraghi 등[24]은 모든 4명의 신경내분비종양 간전이에서 완전 관해를 얻었다고 보고 하였다.

2) 간동맥 치료(hepatic intra-arterial treatment)

간동맥내 치료의 기본 개념은 신경내분비종양의 간전이는 주로 간동맥을 통해 공급받지만 인접한 정상 간은 대개 간문맥을 통해 공급받는다는 것에 기초한다[26]. 따라서 간전이의 영양을 공급하는 원위부 소동맥을 막으면 인접 정상 간실질의 손상을 최소화하고 종양의 괴사를 유도할 수 있는 것이다. PNET의 간전이의 95%는 조영증강 초음파의 동맥기에서 과혈관성으로 보인다. 나머지 5%는 괴사 부분을 포함하고 있어 저혈관성으로 나타나고 이때는 동맥 폐쇄에 덜 민감하다[8,27,28]. 간동맥내 치료는 호르몬 분비 관련 증상이 있거나 빠르게 진행하는 간전이 환자에 있어서 치료에 불응하거나, 절제 불가능한 경우, 수술 후 재발한 경우, 다발성 종양인 경우에 주로 시행된다[29].

(1) TAE

TAE는 미세카테터를 통해 색전물질을 종양에 혈액을 공급하는 영양 동맥으로 보내어 혈류를 차단하여 종양의 허혈과 괴사를 유도하는 치료법이다. 흔하게 이용되는 색전물질로는 미세구(microsphere), 폴리비닐알콜 입자(poly vinily alcohol particles), 젤라틴 스폰지 입자(gelatin sponge particle), 리피오돌(ethiodized oil, Lipiodol®; Guerbet, Villepinte, France), n-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) 등이 있다. 양측성으로 다발성 전이가 있는 환자에서는 한 번에 한쪽 간엽의 종양을 치료하고 최소 4주간의 간격을 두고 단계적으로 반대측 간엽의 종양을 치료하는 것이 일반적이다[7]. 임상적으로 적응증이 된다면 치료는 반복해서 시행될 수 있다[7].

TAE 후 증상 조절률(symptom response rate)은 80-91%로 우수하다[30,31]. Osborne 등[30]에 의하면 총 59명의 환자 중 59%에서 완전 관해, 32%에서 부분 관해를 보였다. Strosberg 등[31]에 의한 평가에서는 48%가 부분 관해, 52%가 안정 병변이었다. 2019년 Zener 등[32]에 의한 연구에서는 160명의 환자 중에서 완전 관해 13%, 부분 관해 40%, 안정 병변(stable disease) 24%로 보고하였다. 즉 완전 관해, 부분 관해, 안정 병변의 합계를 나타내는 질병통제율(disease control rate, DCR)은 77-100%였다[30-32].

중앙 간 무진행 생존 기간(hepatic progression-free survival, HPFS)은 15-36개월이었고[31,33], 종양 등급이 높을수록, 종양 부담이 50%보다 클수록 간 무진행 생존율은 더 짧았다[33]. Strosberg 등[31]의 연구에 의하면 PNET의 중앙 전체 생존 기간은 31개월이었는데, 이는 carcinoid tumor에서의 44개월보다는 짧았으나 저분화 종양에서의 15개월보다는 길었다[31]. 그러나 대부분의 연구들에서 다양한 종양 등급, 종양 조직, 원발 종양 위치, 이전 치료, 질병 부담(diseae burden)을 갖고 있는 이질적 환자 코호트에서 생존율을 평가하였다는 제한점이 있다[7].

TAE의 주요한 부작용은 다양한 정도의 통증, 오심, 구토, 발열, 피로, 간 효소의 일시적 상승을 동반하는 색전후 증후군(postembolization syndrome, PES)이다. 이는 대부분 수일 내 자연 치유되거나 해열∙진통제, 항구토제 등의 대증 요법으로 치료 가능하다. 재원 기간을 연장하는 심한 PES는 9-15% 정도이다[32,33]. 간농양은 0.05-3%에서 보고되었다[31,32,34].

(2) TACE

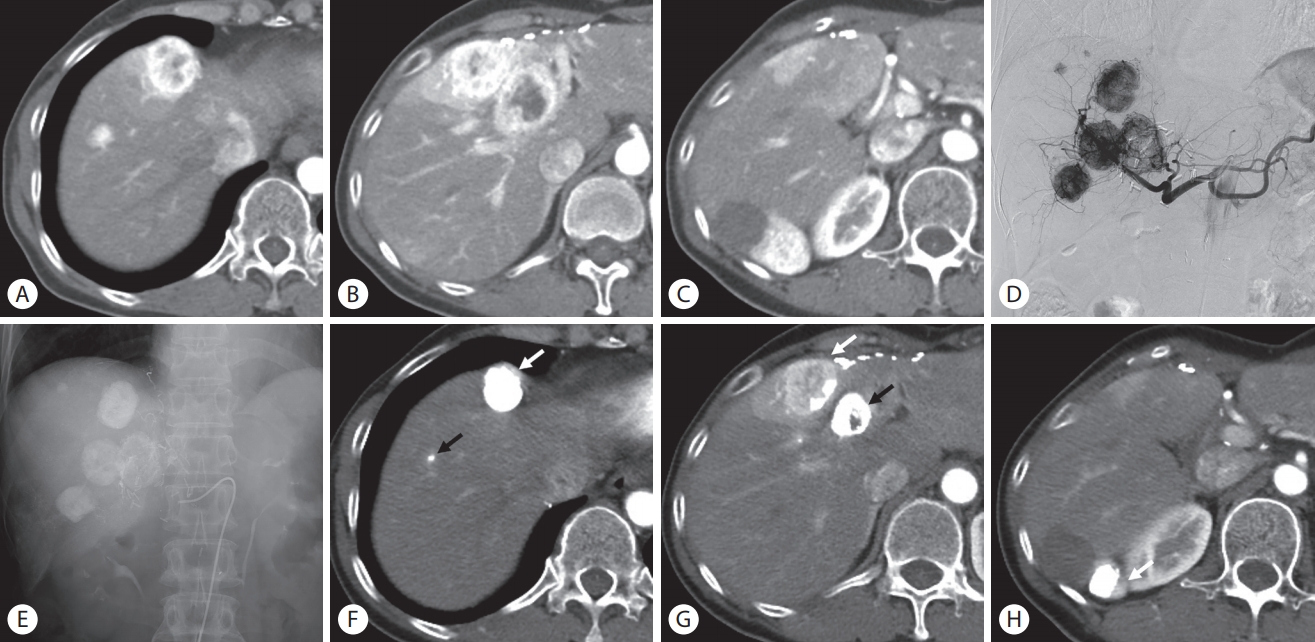

TACE는 두 가지 단계로 수행된다. 먼저 doxorubicin, cisplatin, mitomycin, streptozotocin 또는 여러 항암제 조합을 리피오돌이라는 벡터에 섞어서 미세카테터를 통해 종양으로 혈류를 공급하는 간동맥에 주입하고, 이어서 색전물질을 이용해 간동맥을 색전하게 된다(Fig. 2). 고농도의 항암제를 점진적으로 방출함으로 얻는 세포독성 효과(cytotoxic effect)와 TAE에 의한 허혈 효과(ischemic effect)를 동시에 얻을 수 있다[6]. 색전술로 혈류가 느려지면 국소 항암제 농도를 높여 종양 내에 항암제 정체를 증가시킬 수 있다고 알려져 있다[35,36].

Conventional transarterial chemoembolization (C-TACE) for the treatment of multiple hepatic metastases. (A-C) Arterial phase liver computed tomography (CT) images show multiple hypervascular hepatic metastases in the right lobe and segment IV of the liver. (D) Multiple hypervascular metastases are demonstrated on common hepatic arteriogram during C-TACE. (E) Post-embolization fluoroscopic image shows dense Lipiodol uptakes in the liver. (F-H) contrast-enhanced CT images performed 2 months after C-TACE show that the lesions have decreased in size. Note two lesions with compact Lipiodol retention without residual tumor enhancement (black arrows) and the other three lesions with Lipiodol washout with residual tumor enhancement (white arrows).

TACE 후에 증상 조절률은 54-92%였고[34,37-41], 종양 반응은 완전 관해 0-1%, 부분 관해 43-62%, 안정 병변 24-38%, DCR 71-100%로 보고되었다[7,37-42]. 중앙 HPFS는 8.1-29.7개월[33,37,41], 중앙 OS 기간은 25.5-61개월이었다[33,34,37,39-41]. TACE의 독성은 TAE와 비슷한데, 가장 흔한 것은 PES이며, 간농양은 0.2-6%로 보고되었다[33,34,37,39-41].

지금까지 여러 연구에서 TACE과 TAE의 비교 결과를 발표하였는데, 증상 조절률과 무진행 생존율, OS, 합병증에서 두 치료법 사이에 통계적으로 의미 있는 차이가 없었다[34,42-45]. 그러나 이들 연구들은 소수의 환자에서 다양한 원발 부위의 종양을 포함하였고, 하위 집단 분석을 하지 않았다는 제한점이 있다. 한편, 69명의 위장관 신경내분비종양 환자와 54명의 PNET 환자를 비교한 Gupta 등[44]에 의하면, 위장관 신경내분비종양 환자는 TAE 치료군에서 더 좋은 종양 반응률을 보였으나, PNET 환자에서는 TACE에서 더 좋은 종양 반응률을 보였다. Maire 등의 전향적 무작위 연구에서 무진행 생존율, OS, DCR, 합병증 관련해서 두 치료법 간 차이가 없었지만, 소장의 신경내분비종양 환자를 대상으로 하였고, PNET 환자는 포함하지 않았다[42].

TACE에는 리피오돌-항암제 혼합물을 사용하는 일반적 TACE (classic or conventional TACE, C-TACE)와 항암제를 충진(loading)할 수 있는 작은 미세구(microsphere)를 사용하는 약물방출 미세구 TACE (drug-eluting bead TACE, DEB-TACE) 두 가지 형태가 있다[7]. 약물방출 미세구 TACE의 치료 결과와 합병증은 다른 치료법과 비슷하였는데, 부분관해율은 80%, 무진행 생존 기간은 12-15 개월이었다[46,47]. 그러나 C-TACE와 비교하여 담도 손상과 간경색의 위험도(odds ratio [OR]=6.628(95% confidence interval [CI] 3.699-11.876; p <0.001)와 간괴사의 위험도(OR=35.2, 95% CI 8.41-147.36; p <0.001)가 증가하였다[48,49]. Bhagat 등[50]의 2상 연구는 높은 비율의 담도 합병증으로 인해 임상 시험이 중단되었다. Makary 등[51]은 78명의 C-TACE 치료군과 99명의 DEB-TACE치료군을 후향적으로 비교하였다. C-TACE 치료군에서 더 높은 증상 반응률(54% vs. 30%, p <0.001)을 보였으나, 생물학적 반응(p =0.60)과 영상 반응(p <0.20)에서는 차이가 없었다. PES는 DEB-TACE에서 더 적었으나(67% vs. 50%, p <0.05), 간농양을 포함하는 중대한 합병증은 더 높았다[51]. 그러므로 췌장의 신경내분비종양 환자들 중에서 간창자연결술(hepatoenterostomy)이 시행된 간전이 환자에서는 약물방출 미세구 TAE가 간농양, 간경색, 간괴사 등의 합병증의 위험을 높일 수 있으므로 주의가 필요하다.

(3) TARE

TARE는 베타선을 방출하는 yttium-90 (Y-90)을 포함한 미세구를 종양 공급 동맥에 주입하여 종양에 대한 체내 방사선 치료(internal radiation therapy)와 공급 동맥의 색전 효과를 얻는 것이 기본 원리이다[52]. Y-90 미세구를 주입하는 과정은 TACE와 거의 비슷하나 TACE와는 다르게 TARE 시행 2주 전부터 준비 과정이 필요하다. 먼저 간동맥 혈관조영술을 시행하여, 간동맥의 해부학적 구조 및 변이, 종양 공급 동맥을 파악하고 간외 션트를 확인한다. 이때 치료하고자 하는 혈관 부위에 포함되는 종양과 정상 간의 부피를 측정하기 위해 간동맥조영 CT도 함께 시행한다. 위장관으로 향하는 혈관을 통해 Y-90 미세구가 전달되면 심각한 합병증을 일으키기 때문에 코일을 사용한 예방적 색전술이 필요하고, 주로 색전되는 혈관은 우위동맥, 담낭동맥, 부좌위동맥 등이다[53]. 그러나 위십이지장동맥의 원위부 간동맥에서 선택적으로 미세구를 주입할 수 있기 때문에 위십이지장동맥의 일상적 색전은 더 이상 추천하지 않는다[54]. 또한 동정맥 션트(arteriovenous shunt)가 있을 경우 Y-90 미세구가 폐로 전달되어 방사선 폐렴을 유발할 수 있으므로 치료 전에 폐로의 션트에 대하여 평가해야 한다. 이를 위해 간동맥에 99m technetium-labeled macroaggregated albumin (99mTc-MAA)을 주입한 후 SPECT 스캔을 시행한다. 간-폐 션트분율이 10%보다 큰 경우 용량을 20-40%까지 줄여야 하고, 20%보다 큰 경우는 방사선 색전술이 권장되지 않는다[55]. TAE나 TACE와 달리 방사성 미세구의 색전 효과가 적기 때문에 간동맥 혈류를 유지할 수 있어서 간문맥 혈전증은 TARE의 금기가 아니다. 양측성 질환인 경우 한번에 한쪽 간엽을 치료하고, 4-6주 후에 반대쪽 간엽을 치료하는 것이 중요한데(Fig. 3), 반복 치료는 간독성의 위험이 높아질 수 있으니 주의해야 한다[56].

Combined treatment with conventional transarterial chemoembolization (C-TACE) and transarterial radioembolization (TARE). (A) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver shows multifocal bilobar liver metastases. (B) Celiac arteriogram shows numerous hypervascular metastases in both lobes of the liver during C-TACE. (C) Celiac arteriogram performed 4 months after C-TACE shows decrease in tumor burden, but there are residual numerous hypervascular liver metastases. (D) Right lobe was treated with TARE and left lobe was treated with C-TACE in two treatment sessions, separated by a 4-week interval. Celiac arteriogram shows absence of liver metastases. (E) Follow-up MRI shows a new tiny liver metastasis in segment IV (arrow). Note atrophic change of the right lobe of the liver and hypertrophy of the left lobe of the liver after after TARE in right hepatic artery.

여러 연구에서 증상 반응률은 20-80% 범위였고[57-61], Braat 등[57]에 의한 대규모 후향적 연구에서는 증상 반응을 보인 79% 중에서 44%는 완전한 반응을 보였다. Frilling 등[62]에 의한 최근의 메타 연구에 의하면 평균 DCR은 88% (95% CI 85-90%)였고, 중앙 무진행 생존 기간은 41개월이었다. 870명의 환자를 분석한 Jia 등[63]에 의한 메타연구에서는 86% (range 62.5-100%)의 DCR을 보고 하였고, 중앙 전체 생존 기간은 28개월(범위 14-70개월)이었다. 종양의 등급에 따른 중앙 생존기간 분석에서 G1 등급은 71개월, G2 등급은 56개월, G3 등급은 28개월이었고, 원발 종양 위치에 따른 분석에서는 유암종(carcinoid tumor)은 56개월, 췌장은 31개월, 미분류 환자는 28개월이었다[63].

TARE의 합병증은 주로 방사선 유발 합병증이다. 방사선 폐렴(radiation pneumonitis)은 드물지만 심각한 합병증이다. 간폐 션트 비율이 10% 초과 시 발생할 수 있고, 1-6개월 후 미만성 간질성 폐렴으로 나타난다. 간독성은 지속적인 부작용이지만 대개 무증상인 경우가 많다. 방사선 색전술 유발 간질환(radioembolization induced liver disease)은 13%까지 발생할 수 있고, TARE 1-2개월 후에 황달, 복수 증가로 발현된다. 사망률은 30%까지 달한다[8,55,57,64]. 간경화의 형태학적 징후와 간문맥압 상승은 16%에서 보고되었고, 특히 양측 간엽을 치료하였을 경우는 50%에서 생길 수 있다[56]. Su 등[65]에 의하면 이러한 변화가 생기는 중앙 기간이 1.8년으로 장기간에 걸쳐 지속될 수 있음을 보고하였다. 방사선 유발 혈액학적 합병증은 림프구 감소증(6.7%), 혈소판 감소증(3%) 등이 알려져 있다[57]. 그 밖에 비표적 동맥으로 Y-90 미세구가 유입되었을 경우 방사선 담낭염, 위장관 궤양, 위염 등이 1-4%에서 생길 수 있다[57]. 간부전에 의한 조기 사망도 한 명 보고되었다[63].

지금까지 몇 개의 TARE와 다른 간동맥 치료들과 비교한 연구들이 있으나 전향적 무작위 연구 결과는 부족하다. Engelman 등[66]의 연구에서는 TAE, TACE, TARE 사이에 증상 조절률, 종양 반응률, 합병증에서 차이가 없었다. TACE와 비교한 Egger 등[67]에 의한 후향적 연구에서는 전체 생존기간(TARE 35.9개월 vs. TACE 50.1개월; p =0.3), 무진행 생존기간(15.9개월 vs. 19.9개월; p =0.37), 30일 사망률(2.0% vs. 3.1%; p =1.0) 및 G3/4 이환율(13.7% vs. 22.6%; p =0.17)에서는 차이가 없었으나 DCR (83% vs. 96%; p <0.01)은 TACE에서 더 높았다. Do Minh 등의 연구에서는 성향점수 매칭(propensity score matching) 분석을 통해 HPFS와 전체 생존 기간은 TACE에서 더 길었다고 보고하였다. 한편, Singla 등[68]의 후향적 연구에서 Ki67 점수가 3% 초과인 환자에서는 TACE (53%; 95% CI 10-90%)보다 TARE (88%; 95 CI 40-90%)에서 더 좋은 3년 생존율(OR=0.1; p <0.001)을 보였다.

결 론

전신 치료에도 진행하거나 증상이 있는 절제 불가능한 간전이가 있는 PNET 환자의 치료에 있어 소수의 작은 크기의 병소들은 국소 소작술로, 더 많은 수의 미만성 혹은 다초점성 병소들은 간동맥내 치료술로 치료될 수 있다. 국소 소작술과 간동맥내 치료술을 포함하는 간내 직접 인터벤션 치료들은 증상을 호전시키고 질병을 조절하는 데 좋은 효과를 보였다. 간-창자 연결술을 시행 받은 췌장신경내분비 환자에서 DEB-TACE의 시행은 담도 손상 및 간농양과 같은 합병증 위험이 증가할 수 있다는 것에 주의해야 한다. TARE는 고등급의 종양과 이전 치료들에 불응하는 환자들의 치료에 중요한 역할을 할 수 있다. 다만, TAE, TACE, TARE 같은 간동맥 치료 중 어느 것이 더 효과적인 치료인가에 대해서는 미래의 대규모 전향적 연구 등이 뒷받침되어야 한다. 향후 다학제적 접근을 통해 면역치료 또는 표적치료 같은 전신 치료와 더불어 다양한 인터벤션 치료를 조합한다면 치료 성적 향상을 기대할 수 있을 것이다.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.