내시경역행담췌관조영술로 치료한 복강경 총담관 탐색술 후 Hem-o-lok 클립 이동으로 인한 재발성 담관염

Recurrent Cholangitis due to Hem-o-lok Clip Migration after Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration Treated with Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

Article information

Abstract

총담관으로의 클립 이동은 복강경 수술의 드문 합병증이다. 저자들은 4년 전 복강경 담낭절제술과 복강경 총담관탐색술을 동시에 받은 66세 남자에서 Hem-o-lok 클립 이동으로 인한 담관 결석 1예를 문헌고찰과 함께 보고하고자 한다. 상복부 통증을 주소로 내원한 환자의 복부 전산화단층촬영에서 담관의 확장과 다량의 담관 결석 및 담관을 침범한 이물질이 의심되었다. 내시경역행담췌관조영술을 하여 다량의 담관 결석과 함께 이물질을 제거하였다. 이물질의 정체는 Hem-o-lok clip이었다. 복강경 담낭절제술과 복강경 총담관탐색술을 받은 환자가 상복부 통증을 호소한다면, 드물지만, 클립 이동에 의한 담관 결석 가능성도 염두에 두어야 한다.

Trans Abstract

Clip migration into the common bile duct (CBD) is a rare complication of laparoscopic biliary surgery. We report a case of Hem-o-lok clip migration-induced CBD stone in a 66-year-old man who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) and laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) 4 years ago. The patient visited the emergency room for upper abdominal pain. CT scan revealed increased CBD diameter and multiple CBD stones. We performed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for CBD stone extraction. Cholangiography revealed multiple suspected filling defects in the CBD; stones and unknown foreign body were removed using Basket. The foreign body found in the duodenum was a Hem-o-lok clip. When epigastric pain develops in a patient who has undergone LC and LCBDE, it is possible that biliary stone occurs due to clip migration.

INTRODUCTION

Gallstone disease is common; cholecystectomy is the first choice of treatment for symptomatic gallstone disease [1]. Since laparoscopy was introduced, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has become the gold standard for the management of symptomatic gallstone disease [1]. Over half a million such procedures are carried out annually in the United States [1]. Advances in laparoscopy have made LC+laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) a widely accepted strategy for patients with gallstones and common bile duct (CBD) stone [2]. But clip migration can occur in LC+LCBDE. “Clip migration” is defined as follows: a considerable displacement of the clip (>5 cm) within the peritoneal cavity from the initial placement around the porta hepatis and penetration into the ductal system or a hollow viscus [3]. To date, there have been several reports of clip migration caused by LC with LCBDE [2,4,5]. All cases were reported within 3 years after LC with LCBDE. We report a case of Hem-o-lok clip migration 4 years after LC with LCBDE.

CASE

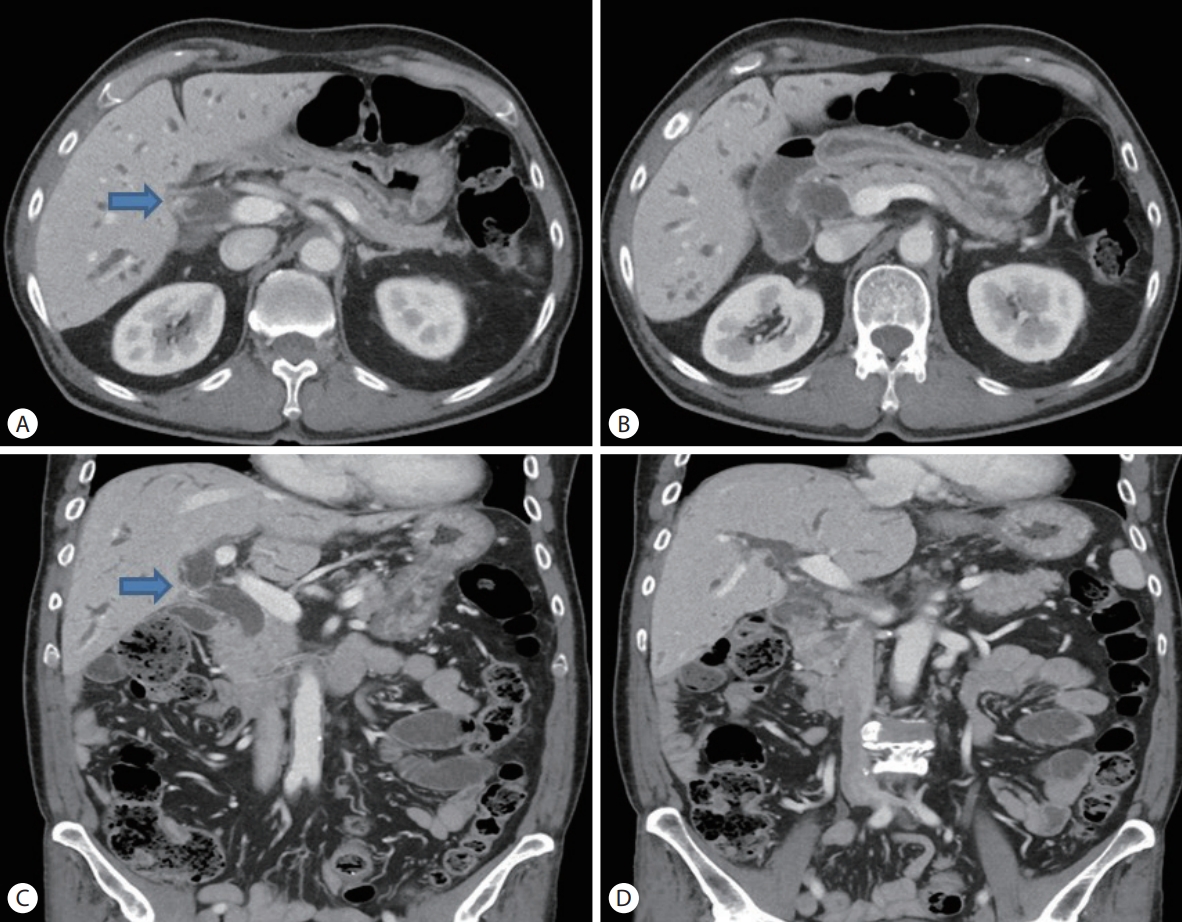

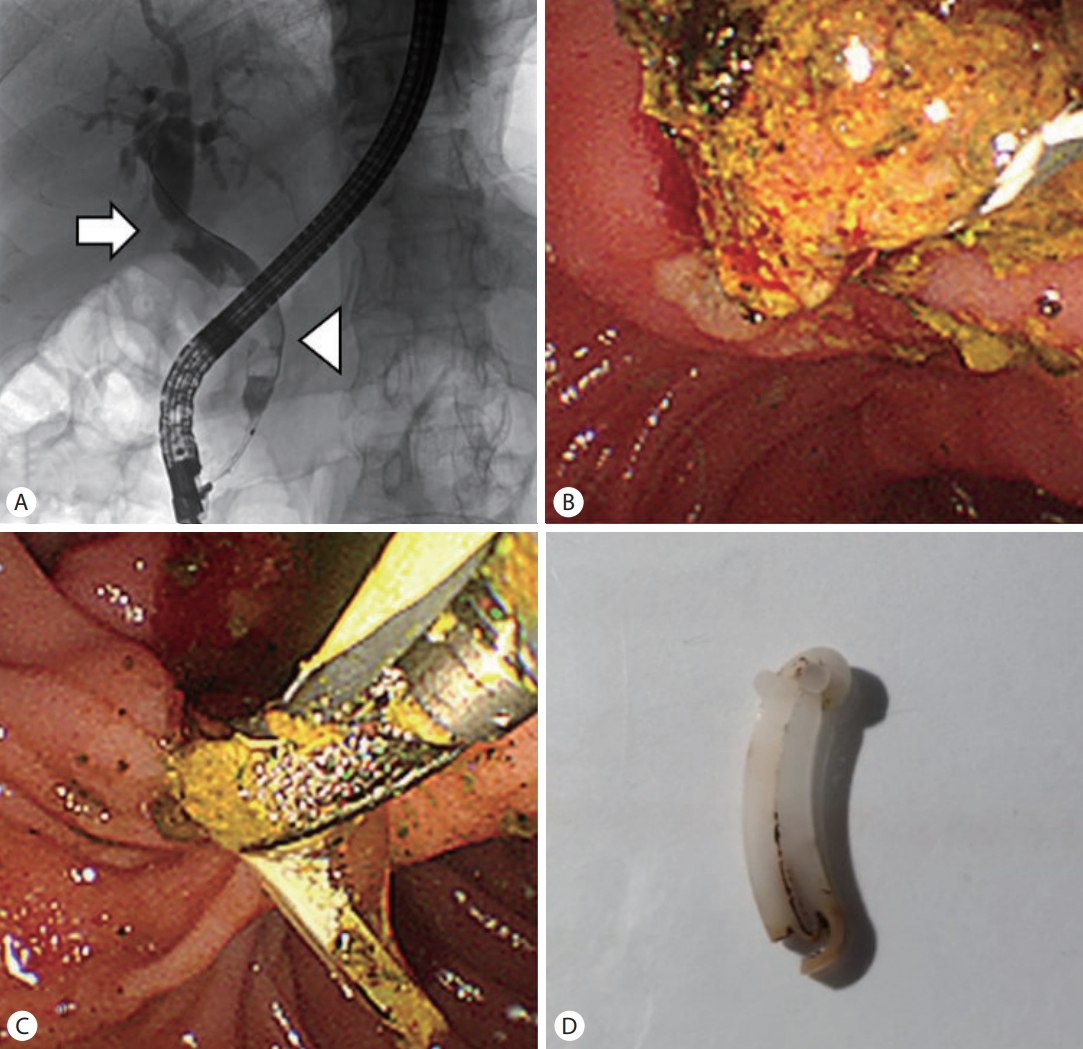

A 66-year-old man visited the emergency room of the Daejeon Eulji University Hospital for upper abdominal pain. He had undergone LC+LCBDE in another hospital 4 years ago and underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) due to CBD stone-related cholangitis 2 years ago in our hospital. Physical examination upon admission revealed an acutely ill looking appearance. His vital signs were: blood pressure, 120/70 mmHg; heart rate, 87 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; body temperature, 37.5℃. The patient complained of pain and tenderness in the upper abdomen, and his pulmonary, cardiac, and bowel sounds were non-specific. The first biochemical analysis revealed a white blood cell count of 11,750/mm3, an aspartate transaminase level of 85 IU/L, an alanine transaminase level of 111 IU/L, an alkaline phosphatase level of 244 IU/L, a gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase level of 1,160 IU/L, a total bilirubin level of 2.99 mg/dL, a C-reactive protein level of 10.66 mg/dL, an amylase level of 28 U/L, and a lipase level of 38 U/L. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed that the patient had multiple CBD stones with proximal bile duct dilatation. An unknown foreign body with focal luminal stenosis encroaching the common hepatic duct (CHD) was suspected (Fig. 1). We performed ERCP using a side-viewing endoscope (TJF-260V, Olympus medical systems, Tokyo, Japan) for decompression of the CBD. Cholangiogram showed multiple filling defects in the CBD, and focal narrowing of the CHD. The clip was fixed at the CHD wall. After removing a large number of CBD stones using a retrieval balloon catheter (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA), an attempt to remove the foreign body was made using the Trapezoid RX Wire-guided Retrieval Basket (Boston Scientific). The extracted foreign body was a Hem-o-lok clip (a type of surgical clip) (Fig. 2). There was not any bile leakage on cholangiogram after removing the clip. But, CHD stricture was suspected. Therefore, a double pigtail 7 Fr×12 cm plastic stent (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was placed above the CHD stricture to reduce the chances of severe stenosis after foreign body removal. He was discharged 8 days after admission; ERCP was performed 2 months later. After the plastic stent was removed, cholangiogram showed that the CHD stricture had improved, compared with the last cholangiogram. Therefore, bile duct biopsy at the CHD stricture site was not performed. The patient was followed up without any complications.

Common bile duct (CBD) stones and foreign body as shown on multidetecto computed tomography (CT). (A) Axial enhanced CT shows the foreign body (arrow) encroaching the common hepatic duct (CHD). (B) Axial enhanced CT shows dilatation of the common bile duct (CBD). (C) Coronal enhanced CT shows the foreign body (arrow) with focal luminal stenosis, encroaching the CHD. (D) Coronal enhanced CT shows common bile duct stones in the distal CBD.

(A) Cholangiogram shows multiple filling defects (white arrowhead) in the common bile duct (CBD) and tight stricture of the common hepatic duct (white arrow). (B) A large number of CBD stones were extracted using a retrieval balloon catheter. (C) The foreign body was extracted using a Trapezoid basket. (D) The extracted foreign body was a Hem-o-lok clip (a type of surgical clip).

DISCUSSION

Approximately 10 to 15% of adult population has cholelithiasis [6]. ERCP for stone extraction is the commonly preferred modality of treatment for CBD stone [4]. Recently, according to the study by Li et al. [7], single-stage surgical strategy such as LC with LCBDE is efficient and safe for the treatment of patients with concomitant CBD stone and gallbladder stone, while avoiding the second procedure. In selected patients, single-stage management for concomitant gallbladder and CBD stones might be considered as the preferred approach [7]. Complications associated with LC have been reported in less than five in 1,000 [8]. They can be categorized into early and late [1]. Early complications include bile duct injuries, bleeding, and wound infections [1]. Late complications include biliary strictures and post-cholecystectomy clip migration (PCCM) [1]. The first case of PCCM was reported in 1978 [9]. Despite the increasing number of cholecystectomies being performed annually, PCCM remains rare [1]; yet, it can be fatal due to risk for cholangitis.

Problems associated with LCBDE have not been clarified yet. There are three possible issues of LCBDE. Firstly, stone may be found in the intrahepatic duct. In this case, intrahepatic duct stone are difficult to remove. Secondly, CBD stone may not be removed completely. Unlike ERCP, which is easy to perform again, it is difficult to perform LCBDE in patients who have undergone LCBDE before. Thirdly, clip migration can occur, as in our case. Since there are few cases of LC+LCBDE, comparison of the ratio of clip migration between LC+LCBDE and LC could not be found in the literature.

Currently, Hem-o-lok clip is widely applied in the controlling of the cystic duct and artery [2]. These nonabsorbable polymer locking clips are inert, nonconductive, CT-compatible, and safe for patients [10]. Since it has better radiolucent properties than metal clips, the migration of Hem-o-lok clip would be more difficult to detect in simple abdominal X-ray or CT. Several reports describe complications related to Hem-o-lok clips, especially clip migration [2,4,10]. Biliary dilatation and strictures have been reported in 74.1% and 28.6% of PCCM, respectively [11]. Strictures were found near the cystic duct remnant. The postulated mechanisms that contributed to PCCM and subsequent biliary complications included: bile duct injuries secondary to inaccurate clip placement, inadvertent placement in the biliary tree, clip slippage resulting in wound dehiscence, bile leak and biloma formation with or without infection, placement of too many clips, and difficult surgeries (either secondary to inflammation, or bleeding) [11]. The mechanism of stone formation include the presence of clip serving as nidus, lithogenic bile, and bacterobilia [11]. All the technical factors in the surgery should be considered to prevent the incidence of clip migration: confirming the structures within Calot’s triangle and their anatomical relationships during dissection, minimizing the number of clips, and avoiding unnecessary surgeries [3]. Management of PCCM with biliary complications is similar to that of non-iatrogenic choledocholithiasis [12]. Based on current recommendations, ERCP should be the modality of choice with surgery or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage reserved as rescue procedures, especially in the presence of difficult biliary strictures or large stones [12]. There may be difficulties when removing the migrated clip. I suggest technical tip for endoscopic removal of migrated surgical clip. If the long axis of the clip is aligned with the direction of bile duct, procedure-related injury during endoscopic removal could be minimized.

In our case, the patient first underwent LC with LCBDE, to alleviate jaundice caused by cholangitis and cholecystitis. After 2 years, he underwent ERCP due to cholangitis. However, at that time, existence of the clip in the CHD could not be identified because the fluoroscopy quality used at that time was low; 2 years later, the patient was hospitalized again, for cholangitis, when it was possible to remove the migrated Hem-o-lok clip. It is thought that the clip acted as a nidus, causing cholangitis.

There is an opinion that single-stage surgical strategy is efficient and safe for the treatment of patients with concomitant gallstones and CBD stones; but, like in this case, LC with LCBDE can cause cholangitis due to clip migration. Ongoing comparative studies between cholecystectomy after ERCP and LC with LCBDE are required and comparison of the incidence and risk of lip-migration between LC alone and LC+LCBDE is also needed.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.